The history of the founding of Mission San Antonio de Padua is quite interesting. Early in July 1771, a little party of Spanish Missionaries, headed by three Franciscan Padres, walked into a beautiful, oak-mantled valley near the coastal region of central California. Here, they pitched their camp and, as was their custom, began to prepare to perform devotional services before the day ended.

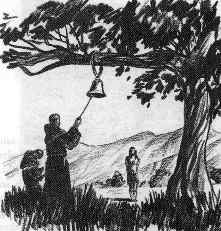

They lifted a large bronze bell from its place upon a mule-pack and secured it to a lower branch of one of the nearby trees. The Franciscan Fathers were more than usually careful in their preparations, for this was no mere overnight campsite. It was to be the site of a new Mission named in honor of Saint Anthony of Padua.

Junípero Serra calls for the Gentiles

As they waited for the approach of the vesper hour, the new arrivals seemed to fall beneath the spell of their surroundings. For a while, no one spoke. Then, suddenly, the oldest Padre leaped to his feet and ran forward to the bell. With all his energy, he rang the heavy clapper to and fro. The woodland silence shattered into a thousand clashing echoes, but the aged men rang on even louder. In a strong, clear voice that matched the sound of the bell, he called to the empty wilderness about him: “Oh, ye Gentiles! Come, come to the holy Church! Come to receive the faith of Jesus Christ”.

His two companions seemed abashed at the old one’s uncontrolled emotion, but they said nothing. The aged man was their leader, Father Junípero Serra, President of the Franciscan Missionaries, who first set the Christian faith upon the shores of Alta California. Finally, the youngest, Father Miguel Píeras, grew alarmed for the well-being of his superior and said, “Why, Father, do you tire yourself? There is not a single Gentile in the whole vicinity. It is useless to ring the bell.”

Dedication of Mission San Antonio de Padua

Junípero Serra turned to him and said, “Father, let me give vent to my heart which desires that this bell might be heard around the world.” Later, Father Serra was happy to learn that his impassioned supplication had reached the ears of at least one Indian “Gentile” on that July day, although his message did not go around the world just then. In 1771, even Father Serra would hardly have expected such a miracle. Thus, it was, however, that the Franciscan Father officially dedicated Mission San Antonio de Padua on July 14, 1771.

With the establishment of Mission San Antonio, the Franciscans aimed at converting to Catholicism the local American Indians of the Salinan tribe. The first written record in 1774 shows Mission San Antonio de Padua doing moderately well. There were, besides some 178 Indian neophytes, 68 cattle, 7 horses, multiple new buildings, and a modest harvest of corn and wheat. A little later, in 1776, the mission was host to Juan Bautista de Anza on the occasion of that intrepid voyager’s second journey overland from Mexico to California.

Together with Juan Bautista de Anza was the Franciscan Father Pedro Font, whose minutely detailed diary gives a clear picture of the daily life within the religious settlement. Father Font bore no strong love for the Native neophytes of San Antonio, whom he found “dirty, not pleasantly formed, and embarrassingly primitive in their mode of dress.” Their language, carefully translated into a written form by Father Sitjar, sounded to the ears of this “civilized” Spanish listener like a series of guttural outbursts.

San Antonio de Padua is a thriving Mission

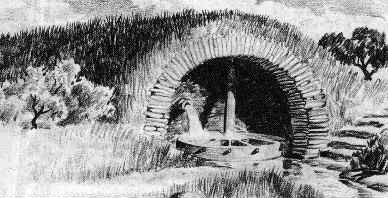

Padres and Indian converts at San Antonio pushed building operations from the start. During the year 1776, they roofed the Mission church with mortar and tiles and completed a street lined with adobe dwellings for the Indians. They erected storerooms, barracks, warehouses, and shops and dug irrigation ditches to carry water to the fields from the San Antonio River.

In 1779, the inhabitants initiated a building 133 feet long for the Mission church and sacristy and finished it the following year. Old records reveal steady progress in building through the years. The Fathers completed a new church in 1813, and long before that, they had already built a water power mill for grinding grain. The Indian community grew steadily and, over the years, dug wells and built a reservoir and aqueduct. In 1825, the heavy rains that fell in the San Antonio district caused the collapse of several adobe buildings. Still, the Mission dwellers soon replaced the collapsed buildings with more extensive and reinforced structures.

Epidemics decimate Indian converts

As Mission San Antonio de Padua grew wealthy and generally improved, so did the arrival of new Indian neophytes. By 1782, the usually irascible Pedro Fages, back in California for another term as Governor, was pushed to remark approvingly on the industry of the mission and the good manners of its converts. A half-century later, in 1830, the valley contained over 8,000 cattle and 12,000 sheep. Its harvests were large, and wine and basket-making were thriving industries. Yet, the number of Indian converts declined over the years because of disease and epidemics.

San Antonio de Padua falls into ruin

After 1834, the mission rapidly disintegrated under the impact of secularization. President Abraham Lincoln signed a patent in 1862 and finally returned the extensive structure to the Catholic Church. But after 1882, when the last resident Priest died, the building was left to the mercy of the elements. Nor did the elements fail to receive a helping hand for, as recently as 1949, it was discovered that a rancho-style railroad station many miles away had been completely roofed with tiles from the mission. The tiles had been sold to the railroad by an enterprising antique dealer and purchased in good faith.

Efforts to restore the Mission begin

In 1903, under the leadership of Joseph R. Knowland of Oakland, efforts were started to save the fading structure. Considerable progress was made until the great earthquake of 1906 damaged most of it beyond repair. Soon, only the front section of the church and a few old arches remained.

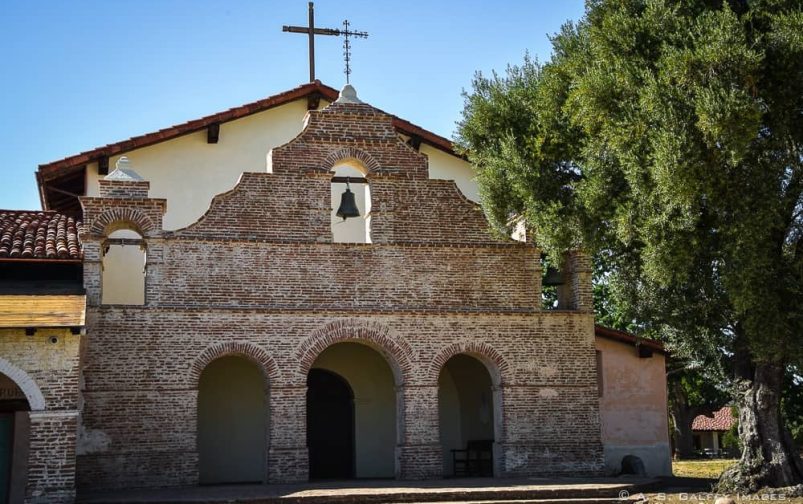

Present reconstruction did not get underway until 1948 when the mission received a grant of $50,000 from the half-million dollar fund set by the William Randolph Hearst Foundation for mission restoration. Today, Mission San Antonio de Padua is merely a reconstruction rather than a preserved ruin. The little hills of earth that once had formed the adobe brick of the original walls were carefully reformed in the same simple fashion practiced by the Padres and their Neophytes 150 years before.

Every piece of timber added to the new structure was cut and surfaced with the same tools the first woodcutters had used. Modern conveniences remain perfectly concealed, and from the exterior, it could be the same humble structure the followers of Father Serra knew so well. The darkness and cold are gone, dispelled by electric light and radiant heating. The bronze bell in the center niche of the Campanario is the first mission bell made in California, weighs 500 pounds, and is 24 inches in diameter. It was created specifically for Mission San Antonio de Padua as part of the restoration works.

California Mission Trails Association

June 4, 1950, is an important date in California mission history. High officials from all over California gathered with thousands of visitors for the dedication of the restored Mission of Saint Anthony of Padua. The California Mission Trails Association, because of the nature of the organization and its place in the life of the California missions, was called to organize and present a fitting program for the commemoration. At the event, the California Mission Trails Association also presented the completion of what is now a living landmark, the “El Camino Real bell marker”. Today, hundreds of these bells mark the historic highway of El Camino Real on its nearly 800-mile route along the Pacific coast.

The Mission lies in an oak-mantled valley

The importance of the repair of San Antonio de Padua extends beyond the mere physical re-establishment of the buildings. It is the only mission whose surroundings remain as they originally were. The oak-mantled valley is still unspoiled, and there is little visible habitation; nothing but the parked cars of the visitors suggests the modern world.

The remoteness of what was redone at San Antonio by the Franciscan Fathers presents problems for today’s visitors. Leaving the little town of Jolon, one must drive several miles through the Hunter Liggett Military Reservation, and past the imposing headquarters building that was formally a Hearst hacienda. The hacienda has been mistaken time and time again for Mission San Antonio de Padua. The actual old mission is still out of sight and a mile beyond.