The host of unconverted Indians dwelling beyond the hills back of Santa Barbara had long been the object of Franciscan concern. So it was that on September 17, 1804, a new mission was founded in the beautiful valley 45 miles north-east of Santa Barbara, and the padres named it Mission Santa Inés Virgen y Mártir in honor of Saint Agnes. By this time the Indians were aware of the missionary effort and when the fathers set their altar in the field, some 200 natives were present to receive the blessing. More than 20 children were baptized on the founding day.

The founding Father Estévan Tápis, who had become superior of the missions following the death of Father Lasuén in 1803, had every reason to expect a prosperous future for the mission. However, Santa Inés did not measure up to the early indications of success. Its span of life was less than 32 years, and its greatest neophyte population peaked at 768. In only two seasons did its grain harvests total over 10,000 bushels and its livestock remained between 9,000 and 10,000 head. Such a mission was hardly poor but it did not fulfill the expectations of the fathers because of the great number of “pagans” nearby.

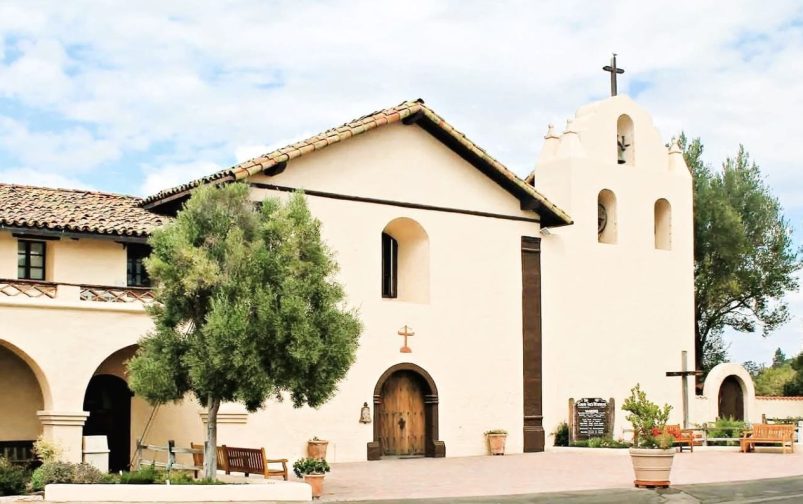

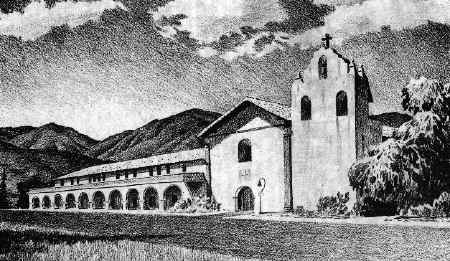

The buildings of the mission were almost completed in 1812 and the church could be seen for miles around. An earthquake that year tumbled the structures into smoking rubble, and the laborious procedure of rebuilding began. It was 1817 before the reconstructed church was dedicated. Water from a stream miles away was brought through ditches and clay piping to two great reservoirs that still stand near the mission. By 1820, prosperity could be seen in the appearance of the fields around Santa Inés, although Indian grievance was rising and soon there would be trouble at the mission.

In 1810, the military in California was cast adrift. Supplies came to the soldiers rarely or not at all and the presidio commanders became increasingly dependent on the missions. This meant more labor for the Indians. In addition, the new governor was encouraging the Indians to ignore the orders of the padres. He also urged his soldiers to take temporal leadership within the missions. The Indians and the soldiers were soon antagonists. In February 1824, a group of well-armed Indians attacked the mission guard and set fire to many buildings. When it appeared the flames would destroy the church, their anger subsided and they helped save the edifice. All the workshops, soldiers’ barracks, and habitations of the guards were destroyed. After causing great destruction at Santa Barbara and La Purísima Concepción, the rebels fled to the Tulares.

In July 1836, the greater part of Santa Inés passed into the hands of the civil administrators and, except for the short and stormy rule of Governor Manuel Micheltoreña from 1842 to 1845, the mission fell upon evil days. While Micheltoreña’s avid Royalist sympathies led him into conflict with the provincials and ultimately caused his flight from California, he was friendly to the padres. Although his restoration of the missions to the Franciscans was generally ignored, it did benefit some of the stations, especially Santa Inés.

Here the governor and the bishop of California entered into a very successful legal arrangement, which may have been deliberately designed to evade the effects of secularization. The governor returned some 36,000 acres of former mission lands, not to the mission but as a gift to the dioceses for the purpose of founding a college of religious education. When Pio Pico sold the last of the mission property in 1846, he had not yet been able to seize the college lands. The college continued as an active seminary, first under the Franciscans and then under the Christian Brothers, until the success of more convenient schools induced the Church to sell the school lands to private owners in 1882.

The church at the mission was never actually abandoned and, in 1882, an astute mission padre invited the family of a stone mason to live at Santa Inés. Soon, there was a notable improvement in the appearance of the buildings and the long process of restoration may be said to have begun at this time. Father Alexander Buckler began a systematic program of improvement in 1904, which continued until his death in 1930. About 1923, the Capuchin Franciscan Fathers were placed in charge of the mission.

In March of 1911, the old mission bell tower, weakened by long neglect and heavy rainstorms, was tumbled to the ground by an earthquake. Fr. Buckler replaced it with a shell-like structure of wood and plaster which, though disappointing at close range, restored the outward appearance of the old tower at a minimum expense. The tower remained in use until 1949 when a part of the $500,000 given to the missions by the William Randolph Hearst Foundation was used for the erection of a solid concrete campanario, which now houses the bells Santa Inés has acquired over the years.

Five Franciscan padres lie buried under the tile floor of the mission church and the scene which surrounds the simple markers differs little from its early day appearance. Many of the wall designs were painted over in a mistaken attempt to clean the church interior. They are now being slowly uncovered to join the majority of decorations which are still in their original state. Several striking wooden figures stand about the church but the place of honor is given to Saint Agnes Virgin and Martyr, who looks proudly down from her niche in the center of the altar. This figure is said to have been created by one or more native artists of the mission.

The historical museum at Santa Inés is one of the best in the mission chain. The excellent condition of many of the items can be attributed to long years of work devoted to the project by Fr. Buckler’s housekeeper and niece, Mary Goulet. Although many of the missions pride themselves on their collection of early vestments, the five years of effort that Miss Goulet gave to the collection repair, and documentation of old ritual garments has produced an outstanding exhibit. There is also an extensive display of Latin missals and handmade parchment music books, some far older than the mission. The old paintings that adorn the walls invite the usual speculation about whether one or more of them might be the neglected work of some ancient master. They have been seen by many visitors with a wide knowledge of art, however, and no one has yet reported a classic discovery.

The old wooden doors of the mission are marked by the wavy indented design that appears throughout the mission chain. This design is not merely a chance decoration, for it symbolizes the River of Life and is there to remind all those who enter of the eternities.