The founding of Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad in the Salinas Valley on October 9, 1791, coincided with the beginning of the Golden Age of California’s missions. Gaspar de Portolá had first discovered the location selected for the new Mission and named it Soledad. While his expedition was camping at the site, a Native Indian approached the explorers and replied to questions with just one word that he repeated again and again.

Origin of the name La Soledad

The Indian’s expression, which sounded like the Spanish word for solitude, “Soledad,” seemed to them very appropriate to the location, and Portolá so marked the site on the maps of the expedition. When Mission Soledad was placed there by Father Lasuén in 1791, it was natural for the Franciscans to name it in honor of Our Lady of Solitude.

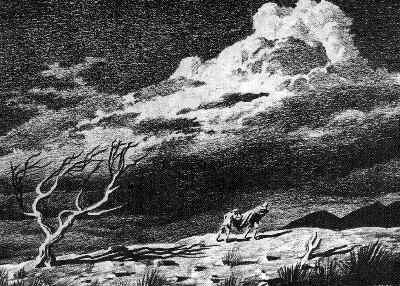

Everything seemed to promise immediate success for the mission establishment in the Salinas Valley. The rolling hills and valley lands that surrounded the site offered the prospect of a limitless bounty. Yet, from the very beginning, the name it had received from a long-forgotten Indian was to be a far more accurate appraisal of its ultimate future than the optimistic aspirations of its Founders.

Founding of Nuestra Señora de la Soledad

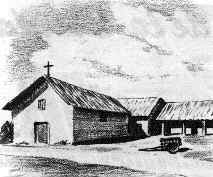

Before Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad was founded, the royal gifts that were to equip the Mission somehow went astray, and once more Father de Lasuén was forced to appeal to the other Franciscan settlements for the needed articles. The brushwood shelter, dedicated in 1791, was not replaced by adobe until six years later. When permanent buildings were finally erected, they tended to disintegrate under extreme climatic changes.

Severe weather destroys the adobe buildings

For instance, the church, which was reported as completely repaired in 1824, collapsed in 1832 as a consequence of severe winter weather. All winter long, the attendant Padres were subject to cold and dampness that the feeble warmth of the few fireplaces could not begin to dispel. Those assigned to Nuestra Señora de la Soledad were soon familiar with the crippling effects of rheumatism and were forced to ask for transfer to more temperate locations.

Father Florencio Ibañez and Mission La Soledad

The notable exception in a history of rapid administrative changes was Father Florencio Ibañez, who devoted more than 15 years of service to the lonely settlement. He is the only Franciscan buried at the site, although the next grave is that of a fellow Spaniard, José Arrillaga, the Governor whom the Franciscans so much admired.

Arrillaga, long beset by illness, seemed to have a premonition of his approaching death. Being unmarried and without family, he moved to La Soledad so that he might spend his last days in the presence of his old friend. Father Florencio Ibañez buried him on July 24, 1814. Four years later, a new grave was dug in the stubborn soil of the lonely Mission, and Father Ibañez was laid to rest beside his friend.

Misfortune and achievements of La Soledad

The Padres of Mission Soledad seemed to find misfortune waiting in every field of effort. The Indians, for whose conversion they labored so strenuously, were not numerous in the area. The highest neophyte population, less than seven hundred, was achieved at the end of 15 years. After 1805, the population of Nuestra Señora de la Soledad began a rapid decline. One of the causes that contributed to the Franciscans’ difficulty was an epidemic, which visited the Mission in 1802. The plague carried off many of the faithful Indian neophytes and drove off many more, who attributed the mysterious malady to their acceptance of the new religion.

Mission La Soledad and Secularization

The secularization decrees in 1834 removed Soledad’s name from the mission rolls, and such records and materials as remained were transferred to San Antonio. In 1846, the site was sold by Governor Pío Pico for just $800. When the United States returned Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad to the Catholic Church in 1859, the property was in such complete ruin that it was never reoccupied. All semblance of human habitation had disappeared, and adobe walls melted into stubs of earth. Talk of one day rebuilding finally culminated in the completion of the chapel, with other restoration in progress.

Father Vicente Francisco de Sarría

Robbed of any singular physical achievement by misfortune and a hostile climate, Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad managed to win a place in California history as the scene on which one of the most sublime and two of the basest Franciscan characters played their parts. The former was Father Vicente de Sarría, whose story is the story of Soledad’s last days, and the latter were two who appeared fairly early in the mission’s life and conducted themselves in such an extraordinary manner that historians have never failed to wonder at their presence in the Franciscan Order.

Father Marino Rubi and Father Bartólome Gili

The story of Father Marino Rubi and Father Bartólome Gili begins in the College of San Fernando to which all California Franciscans belonged. The two friars arrived at the College in Mexico City in 1788 and proceeded to indulge in a series of escapades usually associated with the legendary ones of some undergraduates of our modern universities.

The record indicates that they were a constant source of alarm and discomfort to their fellows, and the charges against them ranged from robbing chocolate from the storeroom of the community to rolling balls through the college dormitory after midnight. It was their habit to sleep during the day when they should have been at their duties, and quite often they would elect to scale the walls of the College and spend the night in town.

The Franciscan Order’s embarrassment

Just why they were tolerated at San Fernando is perhaps explained by the fact that the Franciscans were too embarrassed by their unconventional companions to make it a public matter and that Father Palóu, who headed the College at that time, was too old and ill to be aware of the actual situation. At any rate, the malcontents, who were clamoring for transfer, finally obtained to send the two friars to Alta California. Father Rubi arrived in 1790 and Father Gili the following year.

A year after Father Rubi arrived at Mission La Soledad, his companion Padre very happily exchanged places with Father Gili, who had just come to San Antonio. Once together, the two soon made a reputation for outrageous behavior and their complaints were unceasing. They devoted themselves to sending requests for a return to Mexico. They wailed about the discomforts of Soledad, the worst of which seemed to be the constant shortage of altar wine.

Father Gili ends up in the Philippines

It did not take Father Lasuén long to agree that they would be better off in another place but the Viceroy, who had just approved their transfer to Alta California, was reluctant to have them return to Mexico. In the end, the Royal Surgeon examined the illness claims of the two Padres. Father Rubi was found to have a definite disability and was allowed to depart in 1793. A year later, Father Lasuén received permission for Father Gili’s transfer, and they gladly saw him off on a boat whose Captain, whether by design or not, refused to allow the Padre ashore at Loreto and carried him away to the Philippines.

The Last Franciscan Padre of La Soledad

At the opposite range of human behavior stands the figure of Father Francisco de Sarría, the last Franciscan Padre at Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad. On occasions, Father Vicente de Sarría had served as both President and Prefect of the Missions during the years before Secularization. The disturbances in Mexico and the growing hostility of the Californians put an end to the arrival of new friars and, when he found that it was impossible to find another Padre for Soledad Mission, he decided to take the post himself.

The fortunes of Soledad ebbed even lower, and Father Sarría, alone at the Mission, carried on his work among the Indians until May 1835, when his worn and emaciated body was found lifeless at the foot of the altar. With his death, Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad died also, and a few days later, the last of his loyal Indian followers carried his body over the hills to San Antonio de Padua, leaving behind a lonely group of structures that slowly melted away.

Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad today

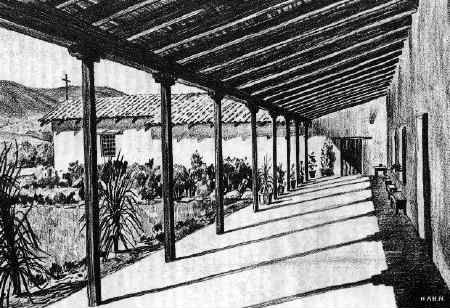

When the reconstruction finally began at the Soledad Mission, only stubs of adobe walls marked the location of the old quadrangle. Today, the chapel and the monastery wing have been rebuilt. Loving care has made the area a garden spot.