On July 1, 1769, Father Junípero Serra and Don Gaspar de Portolá arrived on the shores of the beautiful land-locked harbor which had been named San Diego by Vizcaíño. Of the 219 men who had left Baja California two months before, little more than a hundred had survived, and these were weak, sick, and exhausted by their journey.

To Governor Portolá, San Diego was only a way-stop, and after two weeks rest, he gathered the sound men about him and marched northward to find the long-sought bay of Monterey. He took Fathers Crespí and Gomez with him and left the task of founding the first California Mission at the new settlement to Father Serra. The San Antonio ship went back to Mexico for additional supplies.

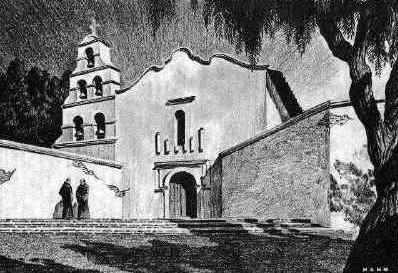

Dedication of Mission San Diego De Alcalá

Two days after Portolá’s departure, Father Serra called upon those still able to move about. With their help, Junípero Serra erected a crude brushwood shelter that, on July 16, 1769, became the first church of Christ in Alta California. The Native Indians, for whose salvation the eager Father had embarked upon the long and dangerous journey, were slow in coming. They observed the evolution of the new settlement with wonder, approaching the strangers with caution.

After some time, the local Indians Kumeyaay grew indifferent to the gestures of friendship made by Father Serra and his Franciscan followers and came only to steal whatever was not resolutely defended. Father Junípero, anxious to win the Natives to him, forbade using arms until an Indian attack in force left no alternative. A few volleys ended all harassment, but the early missionary efforts bore little fruit.

Gaspar de Portolá returns to San Diego Hill

Six months had passed before Portolá returned to San Diego Hill. He had failed to locate the harbor of Monterey. In his absence, little had been done beyond marking 19 new graves. Food and supplies were dangerously low. While the Fathers prayed for the arrival of the supply ship San Antonio, Portolá sent some of his men overland to Loreto for aid. His calculations set the middle of March as the last possible date they could hold San Diego De Alcalá, which, at that time, was still a feeble settlement of Christianity in Alta California.

The little ship San Carlos, unable to sail because of the death of most of her crew, lay in the harbor. After hearing of Portolá’s determination to return if aid did not arrive, Fathers Serra and Crespí talked long and earnestly with the Captain of the San Carlos. They agreed that no matter what Portolá might do, they, and whoever else they might persuade to join them, would remain in San Diego and then sail northward on the small vessel to find Monterey.

A little ship saves Mission San Diego De Alcalá

The sails of the San Antonio were sighted far out at sea just one day before the fateful date of the decision. The ship passed over the horizon, but the vision of the sail had been enough to convince even Portolá that a delay of a few more days might be rewarding. Three days later, the San Antonio put ashore into the harbor. In the tumult of cheers that greeted its arrival, the Spaniards instantly forgot plans and counter plans.

Junípero Serra and Portolá head for Monterey

Within three weeks, Portolá and his expedition set off again for the north. This time, Portolá was determined to find the elusive harbor of Monterey. Once again, he took the hardy Father Crespí with him. Father Serra sailed aboard the San Antonio because its leg, which became infected at Vera Cruz, had become ulcerous during the overland trip from Loreto. During his subsequent journeys along El Camino Real, this affliction was to bring Father Junípero Serra near death on several occasions.

Mission San Diego is in critical conditions

Father Serra left two priests at Mission of San Diego De Alcalá, and they, with three staffers and eight guards, attempted to carry on the missionary work. A year of bitter struggle against illness and the hostility of the Indians left the two Fathers exhausted, and they retired to Mexico. Two newcomers, the Franciscan Fathers Jáyme and Dumetz, took their places.

The situation was critical. Father Dumetz immediately set off to Baja California, to search for vitally needed supplies. When he returned some months later, bringing foodstuffs and a small flock of sheep, Mission of San Diego De Alcalá had already received assistance from the new establishment at Monterey. From this time on, the question of supplies was no longer critical.

Serra leaves the San Diego Mission for Mexico

Other problems began to press upon the Mission Fathers. Governor Gaspar de Portolá sailed to Mexico, ending forever his experience in Alta California. Before leaving San Diego, Portolá handed over to the energetic Pedro Fages his post of military Commandant and Governor of Alta California.

Lieutenant Fages soon began demanding that the Franciscans subject themselves to the control of his office. Father Serra took the controversy to Mexico, and with the aid of his Franciscan College in the Capital, he was able to have Fages removed. However, this did not solve the problem because a fundamental difference in viewpoint was to cause friction and misunderstanding between the Missionaries and the Civil Authorities throughout the entire Mission Era.

While Father Serra was in Mexico on the Fages matter, significant changes were about to take place in San Diego. The Spanish Missions of Lower California passed under the control of the Dominicans, and ten new Franciscans, including Palóu and Lasuén, arrived in Alta California.

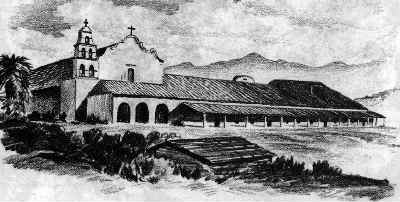

Palóu moves Mission San Diego six miles inland

During his stay in San Diego, Father Palóu, who became acting President in the absence of Father Serra, had moved the mission site six miles inland to relieve the difficulties the Padres were having with the soldiers on Presidio Hill. When Serra returned early in 1774, Fathers Jáyme and Fuster greeted him with enthusiasm. Many Priests had been in charge since the founding of Mission San Diego, but these were to be remembered for a special reason.

Indians attack Mission San Diego De Alcalá

On November 4, 1775, a large force of about 800 Kumeyaay Indians attacked the mission, and a brief and bloody fight ensued in which Natives killed Father Luis Jáyme, a blacksmith and a carpenter. Removed as it was from the Presidio, the bloody conflict at Mission San Diego De Alcalá went unnoticed by the soldiers, who otherwise could have routed the invaders easily.

Mission San Diego De Alcalá is abandoned

The incident impeded further development of the missions. Not only the Mission Fathers were forced to return to the military establishment on San Diego Bay, but even Mission San Juan Capistrano, then in the process of being founded, was abandoned, and its Padres brought to San Diego. As a further result of the revolt, Father Junípero Serra came into conflict with the new military Commander, Rivera y Moncada, who was determined to make a bloody example of the Kumeyaay Indian ringleaders and saw no immediate reason to reconstruct Mission San Diego De Alcalá.

Since the attitude of Rivera y Moncada threatened to intensify the difficulties in winning over the Indians, Junípero Serra opposed the new Commander with considerable energy and won out after months of delay.

Franciscans return to San Diego Mission

The Missionaries did not return to the valley site until July 1776, and in October of the same year, they erected a temporary church. The church building, constructed in the fashion we recognize today as mission style, was not completed until November 12, 1813. It was 29 years after the death of Father Serra, who did not live to see the large tile-roofed buildings that stand today as monuments to his zeal and energy.

Prosperity and decline of Mission San Diego

After the early 1800s, the years that passed were peaceful. At the peak of its prosperity, Mission San Diego De Alcalá possessed 20,000 sheep, 10,000 cattle, and 1,250 horses. It covered an area of 50,000 acres and was renowned for its quality wine. The decline of the San Diego Mission began in 1824 with the encroachment of civilian settlements. Following the Mexican Revolution of 1821, the ambitions of civilian and secular authorities began interfering with the activities of Mission San Diego De Alcalá, culminating, in the late 1830s, with the confiscation of all mission properties under the secularization laws.

Mission San Diego returns to the Catholic Church

On June 8, 1846, the Mexican Governor Pío Pico sold Mission San Diego to Santiago Arguello for “Services to the Mexican Government”. It was not until 1862 when a little more than 22 acres were restored to the Catholic Church by the United States Congress, that Mission San Diego De Alcalá resumed its spiritual function. For the 15 years before restoration, it served as a military garrison for the United States Army.

The 1813 Mission Church still lives today

When restoration began in 1931, only the facade of the church and the base of the belfry remained. The church building and the bell tower were rebuilt in the exact duplication of the 1813 mission church. The restored church incorporated the few original walls still standing. Recently, a long portico was added, which, from a sufficient distance, indicates the size and appearance of the original structure.

A collection of old relics on the Mission premises allows a better understanding of the history of San Diego De Alcalá. While interesting, the collection of relics is not extensive, for most of them are now in the Serra Museum. The latter is a public repository of mission history that stands on the opposite side of the valley, some miles to the west, on the area once known as Presidio Hill, the site of the first European settlement in Alta California.