Mission San Juan Capistrano has the unique distinction of being twice-founded. The first occasion was in 1775 after Father President Junípero Serra had convinced Captain Fernando Rivera that a new mission to interrupt the long journey between San Diego and San Gabriel was urgently needed. Soon after, Father Fermín Lasuén and a fellow Padre were sent from Carmel, and, with the assistance of a small band of soldiers from San Diego, they erected a cross and dedicated the Mission of San Juan Capistrano on October 30, 1775.

San Juan Capistrano was twice-founded

Eight days later, a dispatch arrived from San Diego, interrupting the mission’s brief existence. A group of Indian warriors had attacked Mission San Diego and killed one of the Missionaries, Father Luis Jáyme. Such information was serious in these early days, for a hostile Indian attack of any size might destroy the few feeble outposts and end the Spanish occupation of Alta California. Accordingly, Father Lasuén and his party buried the heavy bells and, taking the remainder of their goods, hurried back along the coast to the presidio at San Diego.

Founding of Mission San Juan Capistrano

One year passed before the countryside seemed peaceful enough to justify a return to San Juan Capistrano. This time, Father Serra was at the head of the founding party. When they arrived at the former site, the Father President was pleased to see the cross still standing. Soon, the bells were recovered, hung from a tree, and mission life began.

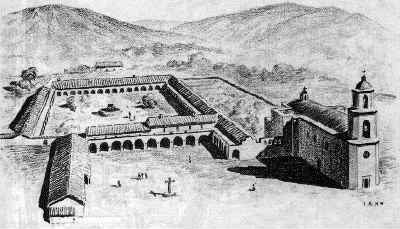

The date of the second founding is November 1, 1776. Due to an insufficient water supply, the same year, the Mission Fathers resettled San Juan Capistrano Mission three miles west, less than 60 yards from the Native village of Acágcheme (also known as Acjacheme). A year later, the first adobe church stood ready for use, and in 1791, the bells were removed from the tree on which they had hung since the founding and placed in a tower.

The first wine ever made in Alta California

Mission San Juan Capistrano is credited to have produced the first wine ever made in Alta California. Vines were planted on the mission grounds as far back as 1779. Some evidence suggests that the first vineyards might have been planted even earlier, just after founding the mission. In 1783, according to records, the winery at San Juan Capistrano produced the first wine ever made in Alta California. The variety of wine produced at Capistrano and other missions became known as “Mission Grape”. This variety was likely obtained by hybridizing the European grape, Vitis vinifera, with wild grapes of California.

Isidor Aguilar and the Great Stone Church

By 1797, the needs of the mission led to plans for a larger church building. The Padres decided that a church of greater proportions was essential. The services of Isidor Aguilar, an expert Mexican stonemason, were secured, and he immediately took charge of the construction.

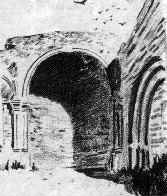

The stonemason enriched the structure with many design features found nowhere at other missions. Instead of the usual flat roof, the San Juan Capistrano church ceiling was divided into seven great domes. Five domes covered the church nave, while two more covered each of the arms and the transept. To provide stone for the construction, the neophyte population spent endless days dragging boulders from the creek beds and valley gullies that led up from the sea. Limestone was gathered and crushed into powder to form a mortar that proved more resistant to erosion than the stone itself.

A quake destroys the Seven Domes Church

The church was nine years in the building when, unfortunately for San Juan Capistrano, the stonemason died. Fathers and Indian converts worked alone for another three years before completing the structure. The Indians and the Padres relied on what they had learned during the previous years. However, the absence of sound supervision caused the irregular measurements of the walls, and the builders were required to add a fifth dome in the nave to even the structure.

The church was completed in 1806, but the inhabitants of the mission were not permitted to enjoy their proud new edifice for long. In 1812, an earthquake nullified the result of nine years of arduous labor by sending the beautiful church crashing to the ground and taking the lives of 40 Indian neophytes. The exhausted Missionaries did not attempt to rebuild the fallen structure but returned to worship in the original smaller adobe church. From then on, the only construction work performed for the mission was nearly always of a functional character. The great piles of ruins, including the soap vats, brick kilns, tannery tanks, and presses, still testify to the vast amount of practical construction.

Bouchard attacks Mission San Juan Capistrano

In 1818, California’s only pirate, Hipólito de Bouchard, assailed the mission. Equipped with two sailing ships, he attacked missions on the coast in the name of a South American Province, which engaged in a revolt against Spain. His connection with the revolutionists was more fiction than fact, but Bouchard found it gave him a convenient excuse for his attack on the settlements in California.

Having been warned of Bouchard’s approach, Padre Geronimo Boscano gathered his Indian neophytes and fled into the interior. The little mission guard made a feeble effort to hold off the pirates and succeeded only in spurring their foes to do greater damage. When the Padres returned, they blamed the soldiers more than the pirates for the conditions in which they found the mission, especially as the wine barrels seemed to be the principal objects of attack.

Mission Capistrano becomes an Indian Pueblo

The good days were slipping by. After the arrival of the Mexican Governor Echeandía in 1825, a difficult period began. He promptly issued a statement advising the Indians they were not obliged to follow the commands of the Franciscans. Thus, discipline, upon which Capistrano’s economy depended, began to break down. When Governor Figueroa chose Capistrano as the site for a Pueblo of free Indians in 1833, mission activity ended.

While the Governor’s attempt to provide the Indians with an opportunity for independence was completely genuine, he failed to provide the legal safeguards that would give them time for adjustment. Had he lived long enough, Figueroa might have succeeded in protecting some of the Indians’ share of mission properties, but he was buried at Santa Barbara less than three years after founding the Indian Pueblo. The land soon gravitated into the hands of the white settlers, and the last of San Juan Capistrano’s property was disposed of in 1845 when Pío Pico sold it to his brother-in-law and a partner.

Capistrano returns to the Catholic Church

In 1865, part of the former mission holdings were returned to the Catholic Church and some attempts were made to halt further decay. The results were ineffective, and mission conditions continued deteriorating until 1895 when Charles Fletcher Lummis, founder of the Landmarks Club, set up a more permanent protection.

Father John O’Sullivan and Restoration

The arrival of Father John O’Sullivan in 1910 was a stroke of exceptional good luck. The new secular Priest was keenly aware of the historical value of Mission San Juan Capistrano, and he worked untiringly to make a worthwhile monument of the former mission. In 1922, he discovered the original little church that, for many years, had been used as a granary and storeroom. Father O’Sullivan started the restoration that ultimately produced the beautiful church still standing on its grounds today.

Serra’s Chapel or Father Serra’s Church

The impressive golden altar, a gift of Archbishop Cantwell of Los Angeles, who had received it from Spain in 1906, and other acquired decorations were added during reconstruction. Of particular interest is the fact that the little church of San Juan Capistrano is the only existing structure in which Junípero Serra has said Mass. Today, it is known as Father Serra’s Church or Serra’s Chapel.

Mission San Juan Capistrano today

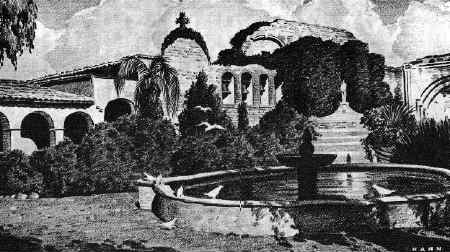

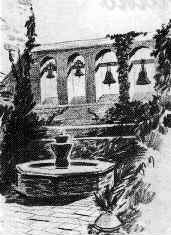

Once the visitor enters the mission grounds, he finds paths that seem to lead everywhere. To the right is the ruin of the great stone church. A stretch of wall and a single dome remain, but they are more than enough to give evidence of the builders’ skill. Nearby is the campanario, or bell-wall, erected in 1813 and still used to ring the mission calls.

The buildings where daily tasks of mission life were once performed attract attention at every turn. Corridors and cloister arches angle off in every direction, leading to the old kitchens, the monastery, and Father Serra’s little church. Throughout the extensive grounds, other relics show the remarkable scope of the mission industries. There are, too, many lovely pools and endless beds of flowers, bearing out to Capistrano the title of “The Jewel of the Missions.”

A group of swallows (Golandrinas) returns each year to the mission premises near March 19, the Day of Saint Joseph. Here, the swallows build their nests on the ruins of the stone church of Mission San Juan Capistrano. Today, a new parish church stands nearby, built in the style of the ruined stone church.