On September 8, 1797, the fourth Mission founded by Father Lasuén in less than three months was named San Fernando Rey de España. Although the Mission was supposed to relieve the long march between San Gabriel and San Buenaventura, the aged Padre set it somewhat to the south because of the barren terrain and poor drainage of the middle area.

San Fernando Rey and Pueblo de los Ángeles

Even the location at San Fernando presented problems. The land best suited for the new Mission was already occupied by a Spanish settler, Francisco Reyes, Mayor of the Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles (today’s Los Angeles). Authorities differ regarding Reyes’ willingness to give up the territory, with some arguing that he had received the grant from the Spanish King, who forcibly evicted him from the Rancho, and others claiming that Reyes had “squatted” on the land and that his retirement was a graceful and obliging one.

The records do show, however, that Francisco Reyes remained long enough to perform the duties of a patron at the ceremony that dedicated the Mission and that he was the godfather of the first child baptized at San Fernando Rey de España.

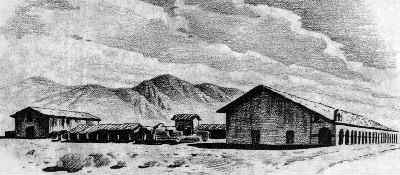

Growth of Mission San Fernando Rey de España

Two months after the dedication, the Franciscans completed building the first church, and Mission San Fernando Rey de España already had a neophyte congregation of more than 40. The Padres and their converts continued to prosper, and by 1806, Mission San Fernando Rey de España was producing hides, tallow, soap, cloth, and other mission products in extensive quantities.

Because they were relatively near the Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles (Los Angeles), they had a ready market to trade with. At the height of its prosperity, San Fernando Rey owned 13,000 cattle and 8,000 sheep, and its 2,300 horses were the third largest herd in the possession of the Missions. These material achievements were not exceptional, however, among the California Missions.

The location chosen for the establishment of Mission San Fernando eventually brought the settlement a unique distinction. Situated directly on the highway leading to the fast-growing community of Los Angeles, it soon became the most popular stopping-off place for travelers on El Camino Real. The number of overnight visits at the prosperous Mission increased so steadily that the Padres kept adding new buildings to the Convento to increase the capacity of the Hospice or “Hotel” facilities.

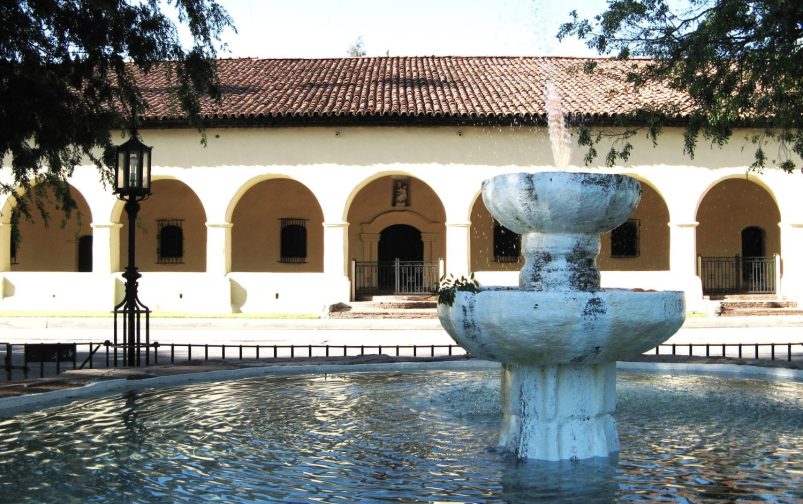

Convento or Long Building of San Fernando Rey

The result was the famous Convento or “Long Building”, which today forms most of the remaining mission structure at San Fernando Rey. Travelers, no matter what their station, were accommodated. A particular room, called the “Governor’s Chamber”, was set aside at the disposal of the most distinguished visitors. This room, rediscovered and restored in 1933, reflects a level of comfort and cheerfulness rarely attained within the thick and gloomy walls of the usual mission structure.

The Neophyte Population begins to decline

After 1811, the neophyte population began to decline, and their lessening numbers coincided with the decreasing productivity of Mission San Fernando Rey de España. Soon, the Mission Padres found themselves unable to fulfill the produce needs of the military headquarters in Los Angeles. Further misfortune occurred during the earthquake of 1812 when a considerable amount of rebuilding was necessary to ensure the safety of the structures.

Father Ibarra and Governor Echeandía

From that time forward the Padres at Mission San Fernando Rey de España fought a losing fight against the encroachment of new settlers. When Governor Echeandía arrived in 1827, Father Francisco González de Ibarra, who headed Mission San Fernando, refused to renounce his allegiance to Spain. He was allowed, however, to remain at San Fernando Rey de España Mission because of the difficulty in getting another Padre to replace him. In 1835, his deep hostility to the acts of the Civil Authorities made him desert the Mission, rather than being a participant in the Secularization process.

Governor Pío Pico leases Mission lands

In 1845, the inevitable distribution of mission property was completed. Governor Pío de Jesús Pico leased the lands to his brother Andres, and later, the land was sold to another purchaser, from whom Andres acquired half of the ownership. For several years, the hospice of Mission San Fernando Rey de España became the summer home of the Governor’s brother. No other mission suffered San Fernando’s subsequent degradation.

Mission San Fernando after Secularization

In 1888, the mission property was used as a warehouse and stable, and later, its grounds and patio became a hog farm. In 1861, the U. S. Government returned the Mission buildings and 75 acres of its land to the Catholic Church. It was not until 1896, when Charles Fletcher Lummis, a prominent member of the Landmarks Club, began a campaign to reclaim the Mission property that the fortunes of San Fernando improved. In 1923, the Oblate Fathers took over Mission San Fernando Rey de España and restored into service the old church.

In the 1940s, the Hearst Foundation granted a bounteous amount of money to fully restore Mission San Fernando Rey. Since then, restoration work has made steady progress. In 1971, Mission San Fernando joined the National Register of Historic Places, and the same year, the San Fernando earthquake caused extensive damage to its structures. Efforts to rebuild the Mission church began immediately, and the working repairs terminated in 1974.

San Fernando has a rich motley of relics

The beautiful “Long Building” of Mission San Fernando Rey de España contains a rich assortment of relics. The great wine press, the smoke room, and the refectory show no deterioration. The hospice still contains the furniture and rude conveniences of its earlier days. The church, just recently restored, presents an impressive picture of the religious phase of mission life. It is somewhat smaller and narrower than the churches of the other missions, but this only adds to its feeling of intimacy and hospitality. The curious irregular sloping of the walls reminds the visitor of the primitive nature of the workmen who built it.

The building contains two other features worthy of special comment. One is a large and somewhat dilapidated organ acquired during its later years, and the other is the altar, the entire lower section of which is mirror-backed. It is said that this mirror, a rather rare decoration at the time of its adoption, was introduced primarily to enable the Padre to keep an eye on his Indian congregation during religious services.

The Altar of Mission San Fernando Rey

Recently the museum acquired a huge altar, over 360 years old, which was brought to this country and stored at San Fernando Rey. Originally 45 feet high and 47 feet wide, the altar is now in several sections, which completely cover the walls of two of the largest rooms in the Mission. The structure is a mass of complicated wood carvings, representing innumerable vines and leaf designs.

Some of these ornaments project from the face of the altar at such a distance that it seems incredible they could have survived without breaking away from the main body of the carving. The entire mass has been covered with gold leaf, which still retains a rich and luxuriant luster. The carving flows in a design around large panels in which oil-painted canvases, some five by seven feet in size, relate to the story of the Holy Family.

Mission San Fernando Rey de España today

Across from San Fernando Rey is a beautiful and spacious park that adds immeasurably to the mission’s importance as a historical landmark. Featured in the park are the old soap works, the original fountain now some 30 feet distant from its first location, and a large, oddly shaped reservoir from which the Mission Fathers were supplied with water. Dominating the entrance to the park is the statue of Father Junípero Serra with an Indian boy.