At a site halfway between San Luis Obispo and San Antonio de Padua, Father de Lasuén founded a new Mission for the third time within three months. It was San Miguel Arcángel, and the founding date was July 25, 1797. The northern half of the Mission Chain, from San Luis Obispo to Dolores in San Francisco, was now completed.

Beginnings of Mission San Miguel Arcángel

San Miguel had most excellent prospects, for it was located in a flat and fertile area near the juncture of two rivers, the Nacimiento and the Salinas. On their arrival, the Mission Fathers found a host of prospective neophytes who welcomed them and helped start the hard work of setting up Mission San Miguel Arcángel. The Padres took this attitude on the part of the Indians as a good omen. Events proved they were justified, for Mission San Miguel Arcángel quickly became a thriving community.

Life at Mission San Miguel Arcángel

In six years, Mission San Miguel Arcángel could account for over 1,000 Indian neophytes. The industrious settlement consisted of many buildings and, as in other missions, Indian converts became accustomed to carrying on several trades. Some Indians became blacksmiths, others carpenters or masons, and the growth of herds of livestock led to the training of soap makers, weavers, and leather workers.

Hundreds of other worked in the fields, the vineyards, or in producing the charcoal used in tile ovens. In the kitchens and the other workrooms, the women performed the routine duties of providing for the daily needs of all who lived there. The Guardian Fathers made constant progress among the Indians, and the Mission prospered without mishap for several years.

A Fire destroys the First Adobe Church

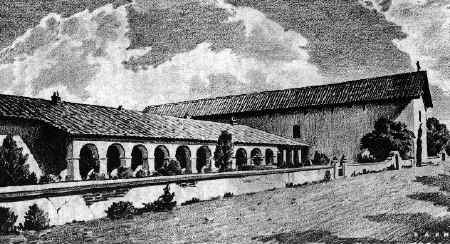

In 1806, a tremendous fire destroyed most of the buildings. In addition, its stores of wool, cloth, and leather goods were lost, and over 6,000 bushels of grain were rendered useless. With the help of other Missions, San Miguel Arcángel soon recovered, and new adobe and tile-roofed buildings replaced those consumed by the fire. The Guardian Fathers started building a new larger church, and by 1816, it stood ready for roofing.

Estévan Munras and the Church of 1818

However, the beams that needed to carry the roof structure could be obtained only in the mountains, the nearest of which lay 40 miles away across a rough and trackless terrain. Little wonder, then, that the Mission Fathers did not complete the church building until 1818. Under the direction of Mission San Carlos’ artisan-builder, Estévan Munras, Indian artists completed the final decorations three years later in 1821. Today, Mission San Miguel Arcángel boasts one of the best-preserved interiors among all California Missions.

The church stretches 144 feet in length and reaches 40 feet in height. The church ceiling is majestic with its monumental 28 sugar pine rafter beams. But the true marvel lies within the vibrant murals that adorn the walls. These artworks utilize a false perspective, creating the illusion of depth and grandeur. Trompe l’oeil flourishes further enhance the visual with painted pillars, balconies, and delicate designs featuring leaves and tassels. Above the altar, a watchful “all-seeing eye of God” casts its rays of light across the space.

Native Artisans and Fresco Painting Technique

The enduring brilliance of these murals is a testament to the ingenious techniques employed by Estévan Munras and its Native Artisans. The paint was meticulously applied using a special glue derived from cattle bones or the fresco technique, where pigments are applied directly to wet plaster. Adding to the unique character of the Mission Church is its unusual arcade, where each arch has a slightly different size.

Father Juan Cabot at San Miguel

Like other inland missions to the north, San Miguel very early developed an interest in the Indians of the valleys of Central California. Father Juan Cabot, who ruled over the destinies of the San Miguel Arcángel Mission after 1800, sent several expeditions into the Central Valley with the idea of establishing a new Mission there. His efforts met with the same hostility that the Padres of the other Missions encountered, and Father Cabot eventually discarded the expansion project. After 1820, the increasing conflict between Missions and Civil Authorities discouraged further development plans. Instead of gaining new areas of influence, the Franciscan Fathers lost all their material gains to the settlers.

San Miguel Arcángel Lands are extensive

Today, the Spanish Missions of California, surrounded for the most part by modern brick and stone structures, present a far different picture than they did 200 years ago. Then, Indians of the San Joaquin Valley were next-door neighbors, living along the periphery of the lands used by the Fathers. A report by Father Juan Cabot in 1827 gives an example of the extent of mission holdings. The report states that the lands of Mission San Miguel Arcángel extended as far as Rancho de la Asunción, a distance of seven leagues to the south, where they joined the boundary of Mission San Luis Obispo.

San Miguel Mission has numerous Ranchos

In this regard, Father Cabot’s account says:

“From the mission to the beach, the land consists almost entirely of mountain ridges… for this reason, it is not occupied until it reaches the coast where the mission has a house of adobe … eight hundred cattle, some tame horses, and breeding mares are kept at said rancho, which is called San Simeon. In the direction toward the south all land is occupied, for the mission there maintains all its sheep, besides horses for the guards. There it has Rancho de Santa Isabel, where there is a small vineyard. Other ranchos of the mission in that direction are San Antonio, where barley is planted; Rancho del Paso de Robles, where wheat is sown; and the Rancho de la Asunción.”

Mission boundaries were nearly 50 miles apart

A Spanish league represents a distance of three and one-third miles. Hence, the San Miguel Arcángel Mission stood 18 miles far from its Rancho at San Simeon, and its north and south boundaries were nearly 50 miles apart. The fertile fields of this extensive area were kept in production by two Franciscans and their Native neophytes, assisted by a handful of soldiers. Yet, San Miguel Arcángel was still far from the largest of the mission holdings; Mission San Luis Rey, for instance, had a rancho at San Jacinto almost 40 Air Miles away from it.

Condition of Indian Converts

To keep this extended program in operation, the Fathers were dependent upon their Indian converts, not as slaves locked up at night and working out the days under the muzzles of Spanish guns, as some writers seem to believe, but as a community of workmen with a system of authority of their own. Only those threatening general security and peace of the Mission met harsh justice and punishments.

It is factual, however, that when Indian husbands went out to one of the Ranchos for an extended period, married women under a certain age had to sleep in the same dormitory with the unmarried Indian girls. The Franciscan Fathers, more often than not, locked the women inside the same dormitory for the night to avoid escapades. The Padres could find no other way of dealing with the pagan understanding of most of their charges, who found it harsh to accept monogamy as a principle of the Christian religion they had embraced.

Decline of Mission San Miguel Arcángel

The last Franciscan left San Miguel in 1840, and Governor Pío Pico sold the last remnants of San Miguel Arcángel in 1846. During the 1860s and 1870s, the long monastery building turned into a series of stores, one of which was the most popular saloon along El Camino Real. In 1878, the property was taken over again by the Catholic Church, and the structures gradually redeemed from the results of their long neglect. The restoration project that began at that time is still underway. In 1928, the Franciscan Missionaries returned to Mission San Miguel Arcángel and, once more, started rebuilding it.

Mission San Miguel Arcángel Today

San Miguel Arcángel Mission has the only church in which paintings and decorations have never been retouched by subsequent artists. The view presented to the visitor, except for the modern luxury of bench pews, is the same as that seen by the Indian converts. In its museum, a great deal of effort has been made to present the tools used in mission industries: branding irons, forging tools, a spinning wheel and loom, a beehive oven, fish traps, and a tile kiln that is still in operation.

One of the most impressive exhibits is a “mission window” used before the Padres obtained glass. It is a wooden frame over which cowhide was stretched thinly, then carefully shaved and greased to increase its translucence. These frames were pegged into the window openings during periods of cold or inclement weather.

The long and leisurely road that formed El Camino Real is today a roaring highway and many of its travelers speed past Mission San Miguel Arcángel without pause. But often a traveler, captivated by the beauty of the adobe Mission and its lovely garden, is moved to stop and discover for himself the wonderful achievements of California’s true pioneers.