As it seemed to fill so many leading politicians and military figures with a desire to become Governor, the change from Spanish to Mexican rule was accomplished with more than a little civil disturbance. The only lasting result was a transfer of authority from central to local control. Within the missions, too, something of the same sort took place. There was divided opinion among the Franciscans on which regime deserved their loyalty. In the end, each Father was allowed to follow the dictates of his conscience without pressure from either side. Within the individual missions, however, a more definite change took place. The Guardian Padres were steadily more inclined to take action for themselves in dealing with problems which, earlier, they would have referred to the Father President or even to Mexico. It was in such an atmosphere that Mission San Francisco de Solano came into existence.

At this time, there happened to be in the mission at Dolores a young Franciscan Padre, José Altimira, one of the more recent arrivals in California. The story of his stay in the Province is brief and turbulent, beginning with his arrival at Dolores Mission. For a young missionary, burning with the desire to make a great harvest of souls, the station near the San Francisco Presidio was a poor place indeed. The narrow peninsula had long been voided of pagan Indians and the needs of the diminishing number of neophytes were more routine than inspiring.

Father Altimira watched with longing the impressive number of conversions by Father Amorós at the San Rafael Asistencia across the bay. Finally, it occurred to him that the poor condition of Dolores presented an excellent opportunity for a change in his situation. Since Dolores was a fading missionary enterprise, he reasoned, why not combine it with San Rafael and place the rejuvenated mission in the fertile area of the Sonoma region further north of the Asistencia?

Father Altimira took his plan to Governor Arguello, who saw in it a desirable means of interposing an additional Spanish settlement between the Russian colony at Fort Ross and occupied Alta California. With the Governor’s approval, the Padre marched into the north to seek an ideal location. After spending some days on the quest, he found a spot that seemed to fit all the requirements. On July 4, 1823, Father Altimira raised a cross on the site that was named San Francisco de Solano.

Father Altimira hurried back to Dolores, prepared for the transfer of the mission, and, on August 12, returned to Solano with a soldier escort and a fair quantity of supplies. By now, Father Amorós of San Rafael and the Franciscan Prefect Senan were actively opposing the steps taken by Father Altimira. Supported by the Governor, the Padre refused to bow before the authority of the Prefect and insisted on going ahead with the project. The controversy ended in a three-way settlement: the retention of Dolores and the recognition of the Asistencia at San Rafael and Solano with full mission status.

Put to the test by the opposition of his superior the obstinate Padre set out to prove the merit of the new mission. A wooden church was erected and formally dedicated in April 1824. This time, however, there was no parade of gifts from the other sister missions. Only Dolores contributed livestock. The new San Francisco found some unexpected benefactors, for the Russians at Fort Ross turned out to be friendly neighbors. They presented the new-founded mission with several articles, including bells of Russian design. Father Altimira persuaded several neophytes to join the new settlement, and nearly 700 Indians followed him from Mission Dolores. Once established, the Padre found himself with everything he needed for success except a leadership capacity.

Father Altimira was soon enmeshed in difficulties with his Indian neophytes, and many of them reacted to his misguided direction of the enterprise by running away or returning to their former settlements. Two years after establishing the mission, Father Altimira impulsively left it in anger fit and dejection. He eventually succeeded in being transferred to Mission San Buenaventura and, a few years later, was smuggled out of California aboard an American vessel.

The mission remained under the direction of the Spanish Franciscans for seven more years until 1833, when the Zacatecas Order of Franciscans took over the operation with Father José Gutierrez in charge. Like other Padres in the San Francisco Bay Area, Father Gutierrez soon felt the effects of Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo’s attacks on his authority over the neophytes. The Padre, who seems to have been neither astute nor kindly in his direction of the mission, attempted to strengthen control by increasing the use of the whipping stick. Such actions merely added to the influence of Vallejo and helped to bring on the secularization of the mission the following year.

As Commander of the San Francisco Presidio, Vallejo was now about all the Government that the Bay Area knew. As soon as Civil Authorities formally took over the missions, Vallejo moved in on the settlement at Sonoma, and soon the most desirable properties were distributed about his ranchos. He announced that they were being held for the benefit of the Indians but when the Official Appraiser arrived at the scene, Vallejo turned him out of the region.

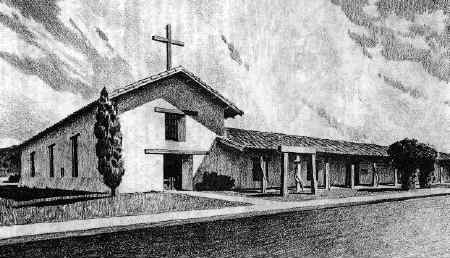

With the founding of the present-day town of Sonoma in 1834, the old mission chapel became a parish church and remained in use until 1880. At that time, a considerable portion of the property was sold. With the proceeds, a modern little church was built while the mission, then in private hands, continued to decay until it was purchased as a California State Landmark in 1910. It now forms a part of the public plaza that has been restored to its appearance of a hundred years ago. The altar of the mission church again looks as it might have long ago. The uneven tile floor of the church has no pews, which is as it was in the past. The Indians stood or sat on the floor. In the cloister wing and quadrangle, items of increasing interest are slowly being added.