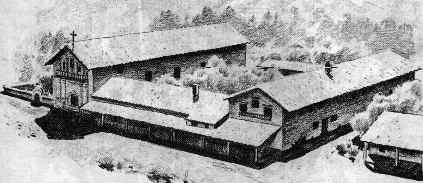

Late in June 1776, Father Francisco Palóu and Lieutenant José Moraga, accompanied by 16 Spanish soldiers, led a small party to the shores of San Francisco Bay. Father Palóu intended to establish a new religious installation, Mission San Francisco de Asís, today better known as Mission Dolores. There were some wives and children of soldiers in the party, as well as the families of Spanish-American settlers, whom Juan Bautista de Anza had induced to try their fortunes in a new colony of California. Bringing up the rear were about 200 weary cattle, herded along by Indian acolytes.

Most of the supplies for the expedition had been sent by sea. The packet ship San Carlos had left Monterey concurrently, but, as usual, the overland marchers arrived well in advance. Without waiting for the vessel’s arrival, Father Palóu and Lieutenant Moraga started their followers on the work of laying out the new settlement.

The origin of the name Dolores

The site selected for Mission San Francisco de Asís bordered a little laguna, or inlet, which de Anza had discovered when he explored the area earlier that year. The explorer named the inlet laguna de Nuestra Señora de los Dolores, a contraction of which became so identified with Father Palóu Mission that, even today, it is far better known as Mission Dolores than San Francisco de Asís.

Dedication of Mission Dolores is delayed

On August 18, the San Carlos arrived, and construction moved swiftly ahead. Permanent mission buildings were completed by September 1, but without a word from Captain Fernando Rivera, the Franciscan Fathers decided to postpone the dedication. Father Palóu and Lieutenant Moraga were aware that Rivera opposed the founding of another mission.

And yet, they also knew that Rivera’s view was not shared by the Viceroy in Mexico City. They had seen a letter to Father Serra in which the Viceroy had expressed the hope that two more missions might be established, one in the name of San Francisco de Asís and one dedicated to Santa Clara. They were confident that Rivera, once sufficiently impressed that these were his superior’s wishes, would hasten to approve their project.

Founding of Mission San Francisco de Asís

After some weeks of fruitless waiting for a word from Captain Rivera, Fathers Francisco Palóu and Pedro Benito Cambón decided to proceed with the formal dedication of Mission San Francisco de Asís on October 8, 1776. Within a year, Father Palóu sent another Padre to establish the mission at Santa Clara while he remained at Dolores Mission. After the death of Father Serra, Father Palóu served briefly at Carmel as President of the California missions before retiring to Mexico City to write the history from which much of this tale was taken.

First converts among the Ohlone Indians

The Mission on Laguna de los Dolores soon became popular among the Ohlone Indians of the area. The Indian natives of the San Francisco district were the least gifted of all the coastal Indigens, and the mission system offered them food and protection from their enemies. As converts, however, they left much to desire. The complex social and religious concepts of the Spaniards seemed beyond their understanding or true concern. The “runaway neophyte” as a mission phenomenon, as well as the Fathers’ method of handling the problem, is treated elsewhere, for it is the basis of many of the charges of cruelty leveled against the Franciscan Missionaries.

Native runaways and desertions are common

At Dolores, the desertions of the “Christianized” Indians threatened the very existence of the mission. The Padres never knew whether their Indian workmen would perform their assignments or flee, and neither, apparently, did the Indians. Torn between the attractions of the nearby Presidio and the unrestrained life of his unenlightened brothers across the bay, the neophyte worker at Dolores was as a reed in the wind. There were many reasons.

Misfortunes of Mission San Francisco de Asís

The narrow peninsula and the recurrent fog caused a drastic limitation on the size and nature of crops. Moreover, the steady growth of the nearby Pueblo of Yerba Buena, today the city of San Francisco, cut off the opportunity for expansion northward, while to the south were mud flats and the Missions of Santa Clara de Asís and San José. The San Francisco de Asís Mission never reached the degree of agricultural prosperity enjoyed by many other missions, and exhausting epidemics, especially measles, took a tremendous toll on the domestic Indians and left the survivors somewhat doubtful of the blessings they received.

A Medical Asistencia is founded across the Bay

After a time, the military officers grew weary of sending soldiers out after runaways, and the subject caused bitterness between the Padres and the Presidio. Both sides realized the behavior of the neophytes demanded some action. An Asistencia, or Mission Rancho, was set up on the north side of the bay where the climate and soil promised benefit to the Indian population. The Missionaries called the Asistencia across the bay San Rafael Arcángel and put in charge of the new establishment a Franciscan Father skilled in medical mastery.

Father José Altimira plans to abandon Dolores

Later, an impetuous Franciscan, Father José Altimira, proposed to abandon both Dolores and San Rafael Asistencia in favor of a third location at Sonoma. The idea received the immediate approval of the Governor, and resettlement was underway before the Father President of the California missions discovered what was happening. The astonished President, now Father Vincente Sarría, pointed out that such an action was beyond the authority of even the Governor. After some discussion, the parties agreed that all three sites would remain as missions, with the Indians given the choice of settling in any of them. And so it was that San Rafael Arcángel and San Francisco de Solano ended up being the last missions in the chain.

Decline of Mission San Francisco de Asís

After the compromise, the fortunes of Dolores rapidly declined. In 1834, the mission finally succumbed to the weight of misfortune which had been accumulating over the years. By the time the land reforms took effect, there was little left except the buildings. When California became a part of the United States, Mission San Francisco de Asís was restored to the Catholic Church, although most of its possessions had long since disappeared.

The Mission survives the 1906 earthquake

Not before long, the once remote settlement of Yerba Buena, now called San Francisco, would sweep around the mission and gather it into its midst. Only then would Mission Dolores achieve a measure of revenge against this lusty city. The day came when the mission stood untouched by the force of the tremendous earthquake of 1906, which shook the surrounding buildings into ruins.

Mission San Francisco de Asís today

Today, all the wounds have healed. In the quiet garden of the mission, the history of the subsequent years is written on the markers of the graves. Victims of the vigilantes have joined early Indian neophytes and rest beside them. Spanish Captains and Irish-American Fire Chiefs have been brought together in this final resting place, even though the church building still belongs to its Founders. Inside, it differs little from its earliest appearance.

The unusually effective ceiling is just as was created by the Indian workmen, and the wooden altars, built in the style of Roman public buildings, have many recessed niches on which stand the sculptured figures of almost all the Mission Patron Saints. Some are long and lean in the figure, like Spanish art, and others reveal the shorter and stockier ideal that developed in Mexico. Some of the latter, definitely not Indian in style, must have been made at Dolores, for they are unquestionably of redwood, a tree unknown in Mexico.

Unknown Artists and Artisans of the Mission Era

Mission history has paid little heed to the artists and artisans who came into the new colony, where they performed countless technical and professional services necessary for its success. Blacksmiths, carpenters, artists, and even engineers gave the mission system its functional design and taught the Indian neophytes to carry on. They did their work, and this is virtually all we know of them, except in rare instances where the records yield a name or two as Estéban Ruíz, builder of Carmel Mission, and Romero and Urselino, the blacksmith and the carpenter who died with Father Jáyme in defending San Diego.

Outside of Dolores, on the busy streets of San Francisco, the steady interleaf of nights and days marks the swift passage of our era. Within the silent walls of the old mission, time has found a stop. Here is yesterday waiting for the traveler where the flight of wooden angels from the altar heights guards his rest.