The original site of La Purísima Concepción, founded by Father Lasuén on December 8, 1787, is not far from the center of the present town of Lompoc. The American Indians of the area were friendly and receptive to the mission system, and numerous neophytes were living on the mission grounds soon after its establishment. A church building was completed in 1802, and within the following decade herds of livestock numbering in the thousands were raised.

Mission La Purísima is moved elsewhere

This notable progress was undone by the fateful 1812 earthquake that destroyed most of the mission buildings and leveled Mission La Purísima Concepción to the ground. The buildings were located near a major fault line, and the violent slipping of the earth masses continued for more than a week. All but the most sturdy equipment was lost or destroyed. The Mission Padres and their Indian neophytes did not wish to rebuild in such a violent location and a new site was chosen at a discreet distance. Four months after the earthquake, the Fathers moved Mission La Purísima Concepción four miles to the north and east where it now stands in the little valley of Los Berros.

Father Mariano Payeras at La Purísima

The hero of the disaster was Father Mariano Payeras, the last of the Friar-citizens of the Spanish island of Mallorca, which had supplied the settlement of California with so many of its great names: Fathers Serra, Palóu, Crespí, and Juan Pérez, the faithful captain of the packet San Antonio. Father Payeras was born in 1769, the year of the founding of San Diego. He had come to La Purísima in 1803, and there he was destined to die some 20 years later.

During his two decades of service, Father Mariano Payeras was President of the Missions for four years and twice served as a Prefect. Like the earlier Franciscan Father Garces, Mariano Payeras loved to march through the unexplored sections of the new territory, visiting Indian rancherias and marking possible locations for future missions. Despite the official prohibition against it, he was friendly to the approach of foreign visitors.

The trade agreement with English merchants

After the Napoleonic conquest of Spain cut off trade with the Mother Country, Father Mariano Payeras, as a Prefect, signed the first trade agreement between the Missions of California and the English merchants. The English signatory, William Hartnell, eventually was to become one of the first prominent citizens of California following its independence and, such is the irony of fate, a leading figure in the Secularization of the Missions after 1833.

Natives seize Mission La Purísima Concepción

At its new site, Mission La Purísima Concepción soon regained its earlier prosperity, and it was not until the year following Father Payeras’ death in 1823, that La Purísima Mission had any further difficulty. At this time, the greatest of all Indian uprisings against the Mission System, known as the Chumash Revolt, touched off by a disturbance at Santa Inés and led the Indians of La Purísima Concepción to seize the Mission.

The Indians resist in a wooden fort for a month

The Indians then demonstrated how well they had learned the construction trades, which the Fathers had so patiently taught them. After driving off the small military guard, they erected a wooden fort and cut holes in the building walls, behind which they mounted a pair of small cannons. Firmly entrenched in their barricade, the Indians held out for nearly a month. It was not until a military force of over one hundred soldiers arrived from Monterey that the Spanish were able to regain possession of Mission La Purísima Concepción. Even then, the surrender of the Indians was accomplished by a Padre who convinced the besieged that they had no chance of holding out.

In all, the incident cost the lives of six Spaniards, four of whom were travelers who happened to be at Mission La Purísima Concepción when the uprising occurred. Seventeen of the Indians were killed in the fighting, and four of the captured ringleaders were put to death for their part in killing the travelers.

Mission La Purísima under Secularization

Once the Spaniards suppressed the uprising, Mission La Purísima Concepción returned to its accustomed routine. The period of its greatest prosperity had passed, however, and ten years later, in 1834, Mission La Purísima Concepción was in the hands of the Secular Administrator. For a time, Franciscan Fathers continued to occupy their residence building, even though the Indian neophytes had disappeared and the church and other buildings were allowed to tumble into heaps of rubble. Ultimately, the last occupants abandoned the once prosperous rancho, and such was its eventual desolation that the property was offered for sale after it returned to the Catholic Church.

Restoration of the Mission began in 1934

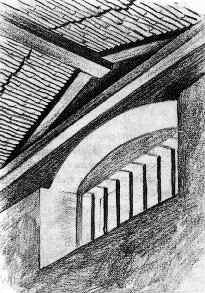

In 1934, 500 acres of the former mission property were acquired by the County of Santa Barbara, and with the cooperation of the State and the United States National Park Service, a program of restoration was begun. A Civilian Conservation Corps camp was located on the spot and the young men began the work of rebuilding. On July 7, 1935, the first adobe brick was laid, and construction of the first unit of the monastery, based on painstaking research, was started. The monastery building alone required the molding of 110,000 adobe bricks, 32,000 roof tiles, and 10,000 floor tiles.

The work of the Civilian Conservation Corps

Instead of destroying the existing ruins, they were incorporated into the new buildings. As a result, the visitor can compare the later cloister columns with the original, and only a careful inspection will reveal the difference. Once the Mission structures were completed, the young craftsmen turned to the creation of furniture, and everything was made as an exact copy of pieces in other Mission museums. The monastery, the church, and the endless row of rooms that housed the soldiers and the Indian neophytes have been restored to their original condition. Now, Mission La Purísima Concepción offers the traveler an excellent opportunity to comprehend the size and scope of a large mission establishment.

Rebuilding the water system of La Purísima

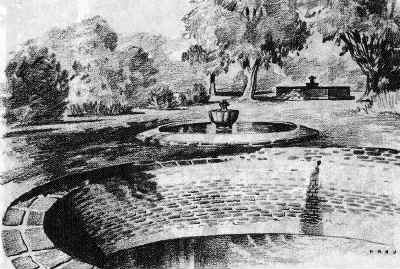

Once the workers of the Conservation Corps restored the adobe structures, they turned to the re-creation of the mission gardens. They began by rebuilding the original water system that collects water from springs placed more than a mile above the Mission and leads it through the gardens and onto the grain fields below. On its course, the water is first introduced into a charming fountain. From there, it flows into a broad circular pool whose sloping stone banks formed the laundry where the Indian women did the mission wash. After passing through a huge settling pool, the water stream continues so to irrigate the fields.

The finest collection of early California flora

The gardens represent a great deal of research by eminent horticulturists, headed by Mr. E. D. Rowe of Lompoc. Every shrub and tree in the garden was known to the Mission Padres and could have existed here at the time the mission was in its active state. Today, this garden is considered the finest collection of early California flora in existence and is well worth the visitor’s time and study.

Mission La Purísima Concepción today

Mission La Purísima Concepción is now a State Historic Park operated by the Division of Beaches and Parks, with an area currently encompassing 967 acres. A remarkable docent program welcomes visitors. The docents, all volunteers, assume the roles of mission residents of the 1820s. In Historic dress, they conduct tours, spin and weave wool, produce mission-period iron tools in the blacksmith shop, and much more, including an outreach program.