Santa Barbara, like San Diego and Monterey, was listed on the Spanish maps of California long before the arrival of the Franciscan Friars. It had been so named by Sebastian Vizcaíño, some 60 years after its discovery by Cabrillo in 1542. From the time of the first march of the Portolá expedition, it had been warmly regarded as a likely spot for mission settlement.

Felipe de Neve halts Mission Santa Barbara

The Padres, however, were 13 years in California before an opportunity for founding a mission at Santa Barbara occurred. By then, Governor Felipe de Neve was their arch-enemy, who openly preferred civil colonists to mission neophytes. Nevertheless, he had agreed at a meeting in San Gabriel to allow the Fathers to place a mission at San Buenaventura and Santa Barbara, although his true interest was in the new presidio he planned to establish on the latter site. It was agreed that all three establishments would be instituted by one expedition.

The Presidio of Santa Barbara is founded

The Padres and their military escort started from San Gabriel in the spring of 1782, but eventually, circumstances prevented the Governor from participating in the founding of Mission San Buenaventura. When the Governor finally met the expedition at Santa Barbara, the new Presidio was quickly established with Father Serra an eager participant in preparing the military chapel.

After the Presidio at Santa Barbara had been completed, and the Governor did not make a move toward the creation of the projected Mission, Father Junípero approached Felipe de Neve and asked him when he intended to order the work on the Mission. The Governor replied that the Mission of Santa Barbara could wait until the Franciscan Fathers were willing to follow the new “Reglamento” which had been ignored at Mission San Buenaventura.

In his heart, Junípero Serra probably knew that the other would never give in, and since the Governor had won the field at Santa Barbara, there was nothing for the defeated Padre to do but return to his headquarters at Carmel.

Fermín de Lasuén becomes Father President

It was five years before the Father President received word that a mission would at last be placed at Santa Barbara. By that time, Felipe de Neve was gone and his place had been taken by the former Governor, Pedro Fages. Some years before, Father Serra had made the long trip to Mexico to secure Fages’ removal, and it must have been a discouraging experience for the aging Padre to learn that his former enemy had returned. The old Franciscan Father did not survive Pedro Fages’ appointment for long, as he passed away on August 28, 1784, leaving the burden of mission problems to be shouldered by the able and willing Father Lasuén.

The administration of Father Fermín de Francisco Lasuén has often been called the “Golden Age” of California’s mission system. Although this period extended considerably beyond the 18 years of Father Lasuén’s Presidency, it was his constructive energy and executive ability that set the pattern for prosperity.

Founding of Mission Santa Barbara

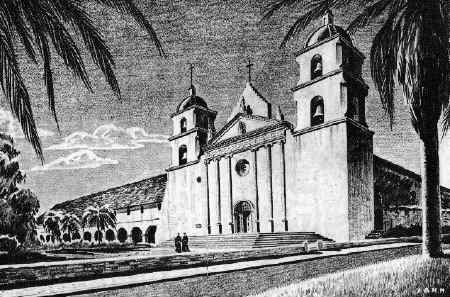

Santa Barbara became an active mission on December 4, 1786, and was the first founded by Father Fermín de Lasuén. Launched on the threshold of the prosperous years, the mission enjoyed singular good fortune from the very beginning. Its first permanent church, finished in 1789, was a well-constructed adobe with a red tile roof. Within five years, the church was too small for the increasing mission population, and a larger edifice was built.

The stone church of Mission Santa Barbara

The structure was destroyed by an earthquake in 1812, and the existing stone church was begun shortly thereafter. Completed in 1820, it remained intact for 105 years. In 1925, an earthquake shook the building so severely that restoration required more than two years before completion.

The design on the facade of Santa Barbara’s church, strongly resembling an ancient Latin temple, was inspired by one of the buildings in Rome of the pre-Christian era. One of the Franciscans had brought from Spain a reprint of a book on architecture, originally published 27 years before the birth of Christ by the Roman architect, Vitruvio Polion.

Chumash Indians and Santa Barbara Mission

The Indians of the Santa Barbara region, the Chumash People, found the mission system much to their liking. Shortly after the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Mission had more than 1,700 Native neophytes living in some 250 adobe houses. They were, like those at Ventura, a more adaptable and energetic tribe than any with whom the Padres had previously dealt. With the ready assistance of their neophytes, the Franciscans soon made the Mission self-sustaining. Part of their industry, a large stone reservoir, is still an active unit in the Santa Barbara city water supply system.

Pirate Bouchard spares Mission Santa Barbara

In 1818, one of the Padres at the Mission was warned of the approach of the French Pirate Hipólito de Bouchard. He armed and drilled 150 of his Indian neophytes in preparation for the expected attack. With the aid of these colorful reinforcements, the presidio guard was able to impress the usually reckless Bouchard, and the pirate sailed out of the harbor without venturing to attack the settlement. This episode was, however, the last instance of cooperation between the Indians and the military.

The Creole resentment against Spanish-born

News of the Mexican Revolt arrived in 1822, and from that time onwards the Franciscan Fathers had increasing difficulties with the Presidio. One of the causes of the friction had little to do with contemporary problems but was deeply rooted in the past. For more than 200 years, those who had been born in the Americas had harbored a smoldering antagonism toward the Spanish-born. This resentment resulted from the fact that the Spanish Kings, feeling that Spaniards would be more loyal than colonials, had always sent from Spain the officers who occupied positions of authority. The Spanish-American “creoles,” no matter how wealthy or influential, were kept out of the profitable administrative positions.

Mexican law bans all Spaniards from California

After the Mexican Revolution, Creole resentment was reflected in an active campaign against the Spanish-born, and one of the first official pronouncements to reach California was a law ordering all Spaniards under 60 to leave the province. Although the order was never executed, it added considerably to the problems of the Padres, for they were all from Spain. Their authority over the Indians was subjected to attack, and soldiers were encouraged to assume the work of policing the Natives. Trouble between Indians and soldiers was inevitable.

The Chumash Revolt and Santa Barbara Mission

In the spring of 1824, an Indian uprising against the increasing violence of the soldiers occurred at three missions, including Santa Barbara. It was the greatest Indian rebellion on record and became known as the Chumash Revolt. At Santa Barbara, the Indians broke into the almost forgotten armory and succeeded in overcoming the mission guard. In the struggle, two soldiers were wounded. The Spanish reprisals were so severe that all the Indians who were not caught fled from the area. It was not until six months later after a general pardon for the Indians had been secured by the Franciscan Father President, that any of the neophytes returned to the mission.

The Zacatecas are put in charge of the Mission

The great days enjoyed by Santa Barbara were fast coming to an end. The withering effect of secularization soon overtook the settlement, although two men were destined to save it from the destruction that fell upon most other missions. In 1833, the Spanish exclusion policy was followed by the introduction of American-born Franciscans, the Zacatecans. The new Governor, José Figueroa, brought with him 10 Zacatecan Friars from Mexico, who were placed in charge of all the missions north of San Antonio.

Headquarters are moved to Santa Barbara

Shortly after this, Father Narcisco Durán, then President of the California Missions, moved his office to Santa Barbara. Here, the courageous Padre conducted a last struggle to save the mission system. In 1842, Francisco Garcia Diego, the first bishop of the Californias, also moved his headquarters to the Mission at Santa Barbara. The presence of both the Bishop and the Father President saved Mission Santa Barbara from complete expropriation until 1846 when both good men died within a month of each other.

The Franciscan Order remains at the Mission

At that time, the ever-eager Pío Pico rushed in to make a final sale. He was too late, however, for California became a territory of the United States before the buyer could occupy his newly acquired property. Santa Barbara, the Queen of the Missions, thus became the only Mission to remain in constant occupation by the Franciscan Order from the day of its founding until the present time.

Mission Santa Barbara today

Having been in continuous occupancy, the Mission closely resembles its original appearance. This is especially true for the interior, where even the rooms that house the Mission’s museum have been in uninterrupted use for more than 200 years. It is logical that the museum’s collection, as the result of these long years of accumulation, should be the best organized and documented.

Each room in the museum has a central theme. The music room, for example, contains an extensive collection of instruments and music manuscripts, with most of the latter bearing distinctive hand-lettered square notes. The music books from which the Indians were taught to sing have each note of the scale lettered in different colors. Other rooms have Indian exhibits of the Pre-Mission Era, such as hollowed stone vessels and ancient tools.

At the back of the old church is the choir loft where the Indian neophytes once sang. The beauty of the interior from this height is most impressive. The unusual decorative effects that give the impression of marble are nowhere more striking than here in Santa Barbara.

Santa Barbara is the Queen of the Missions

Beautiful candelabra are suspended from the ceiling by ingenious “S” shaped chains. At the point where the chains are fixed into the ceiling, one sees the startling “flash of lightning” design resembling the Aztec Indian motif. It is hard to believe that its weird, arresting beauty once graced some ancient Roman wall and that its presence on the mission ceiling reflects the debt of some Franciscan Padre to Polion’s work of 2,000 years before.