The Franciscans had selected an attractive meadowland in the area immediately south of San Francisco Bay as the site of Mission Santa Clara de Asís. Its actual settlement was another matter, though. Father Palóu, willing to set up his mission at Dolores despite the objections of the military Commander Rivera, decided against the founding of the second mission until he had talks with Fernando Rivera, especially as Father Serra was still absent in Mexico.

San Francisco Mission was three months old before Father Palóu had the opportunity to learn the will of the military Commander. At that time, Fernando Rivera came up the coast to give his tardy approval of everything the Missionary had done under his sole responsibility. The Captain’s new attitude would indicate that he had received pointed instructions from the Viceroy in Mexico, for he seemed happy with Dolores and sent Lieutenant Moraga and Father Tomás de la Peña to found the Mission of Santa Clara de Asís.

Founding of Mission Santa Clara de Asís

Mission Santa Clara de Asís joined the growing chain of Franciscan settlements on January 12, 1777. Although the founding of the Mission is commonly attributed to Father Junípero Serra, Father Tomás de la Peña held the first Mass in a makeshift altar built under a tree on the banks of the Guadalupe River. Father Tomás de la Peña founded the Mission under the name “Mission Santa Clara de Thamien” at the Costanoan village of Socoisuka.

The first buildings consisted of a spartan log church and a few corrals. From the time of his dedication, Mission Santa Clara de Asis had six different churches and was relocated five times. Ohlone people inhabited the land where the Franciscans established Mission Santa Clara. During the Mission Era, Santa Clara de Asis would recruit Native neophytes from the Bay Miwok, Tamyen, and Yokuts tribes.

Second mission site with wooden church (1779-1781)

Numerous overflows of the Guadalupe River convinced the Resident Fathers, Tomás de la Peña and José Antonio Murguía, to relocate Mission Santa Clara de Asís to higher grounds. In 1779, the Fathers relocated the early mission to a temporary site where they erected a second wooden church. On November 11, 1779, Father Serra came to Mission Santa Clara de Asís and blessed the small wooden church.

Third mission site with adobe church (1781-1818)

In 1781, the Fathers moved the mission compound to a third site far away from the Guadalupe River to be safe from floods but close enough to allow an irrigation trench to bring water to the mission fields. On this new site, the Mission Fathers immediately began the construction of an imposing adobe church. Father Serra held a sumptuous ceremony at the site, during which he blessed and laid a cornerstone containing religious images, a crucifix, and Spanish coins to symbolize the Church treasury.

In 1911, a workman accidentally found the cornerstone while digging a trench. Today, the cornerstone and its contents are on display in the de Saisset Museum on the Santa Clara University campus. The third Mission church was completed in 1784 and was 100 feet long, 22 feet wide, and 20 feet high. Unfortunately, an earthquake destroyed the church in 1818.

Fourth mission site with adobe church (1818-1822)

With seemingly boundless energy, Padres and Indian converts relocated Mission Santa Clara de Asís some miles away near the present site of Kenna Hall, inside the campus of Santa Clara University. Here, the Mission Fathers began the construction of a fourth set of buildings and a fourth temporary adobe church. The church remained in use until 1825.

Fifth mission site with adobe church (from 1822 onwards)

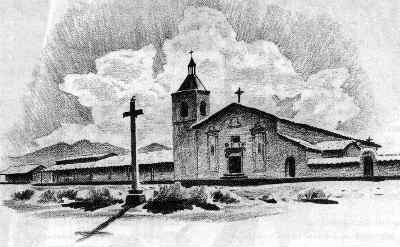

In 1822, the Franciscans decided to relocate Santa Clara de Asís once more and rebuilt it in the form of a large quadrangle at a nearby new site. In 1825, they completed building a fifth adobe church, the last church built during the Mission Era. The adobe church had a square bell tower to the left of its entrance and remained intact for many years. The original 1825 adobe Mission church underwent many remodelings over the years.

By the time of its final ruin, Santa Clara had long since been transferred from Franciscan to Jesuit authority. The Jesuits took over Santa Clara de Asís in 1851 and converted the mission grounds into a college that would later evolve into Santa Clara University. In 1861, the President of Santa Clara College attached a wooden façade with two bell towers at the front of the mission adobe church. In 1885, another President of the College removed the original adobe nave walls to increase its seating capacity. In 1926, a fire razed the church structures to the ground.

Sixth church (present concrete church)

Rebuilding at the same site started soon after the fire, and in 1928, a rebuilt and restored Mission Santa Clara de Asís was dedicated. The sixth and present church was remodeled in the style of the original 1825 church but with some meaningful differences. The structure is wider than the original and made out of concrete. Despite that, the sixth and present church well recalls the last Mission Era church, with a similar façade and a single left bell tower.

Pueblo of San José de Guadalupe

The Santa Clara de Asís Mission was in existence for less than six months when Lieutenant Moraga returned with a group of de Anza colonists, who had been waiting at San Gabriel. Moraga had received instructions to found a new pueblo, San José de Guadalupe, close by the mission, and he accomplished this duty without delay.

Moraga’s pueblo has long since been known as the prosperous city of San Jose, but its founding drew little applause from the fearful Padres. They knew too well the distracting influence it would have on their Indian neophytes. They also knew they could look forward to lengthy disputes over land boundaries. It was not until after 1801 that an official survey fixed the division of lands between the pueblo and the mission.

Nonetheless, during the rebuilding of the Mission compounds at the third site, and for the adobe church completed in 1784, the Padres undoubtedly received the aid of skilled workers from the Pueblo of San José, for the buildings were unusual in their elaborate and finished appearance.

Faulty call from a group of Mission Indians

In May 1805, the Fathers of Mission Santa Clara de Asís became aware that the unconverted Indians were planning a general massacre. The Franciscan Fathers sent a hurried call for help to Monterey and San Francisco, and Spanish troops hastened to Santa Clara from both Presidios. However, an investigation proved that a group of Indian neophytes had spread the wild yarn, hoping to escape punishment for their misdoings by frightening the Padres.

The episode of Father José Viader

At this time, Father José Viader, a powerful and athletic Padre at Santa Clara, gained renown. One night in 1814, a towering Indian known as Marcelo and his two companions attacked him. The Priest bested his three antagonists in a terrific rough-and-tumble fight and then forgave them. After this episode, Marcelo became one of the Father’s most devoted followers.

Prosperity and decline of Santa Clara de Asís

As a mission, Santa Clara de Asís had gone through an extended period of prosperity after 1784 and was second only to San Gabriel in the wealth of its possessions. It was especially known for its fine weaving.

In the 1830s, Santa Clara de Asís began to decline, suffering the same withering destiny that fell to the other missions when the California Dons cast off the restraining yoke of the Spanish throne. The mission disappeared under the Mexican flag until it was restored to the Catholic Church by the American Government. Although it has been used as an educational institution since its occupation by the Jesuits in 1851, it was not recognized as a college until 1855 and thus missed by four years the honor of being California’s first institution of higher learning. Today, it enjoys both a scholastic and athletic reputation far exceeding the proportions expected from a school of its size.

The tragic death of Captain Fernando Rivera

When he gave his belated approval to the establishment of Mission Santa Clara, Captain Fernando Rivera y Moncada was already in the process of being transferred. Due to Father Serra’s opposition, orders were already underway to remove him from the military command of Alta California. In this position, he had been under the jurisdiction of Governor Felipe de Neve in Lower California.

The new directives moved the Capital and Felipe de Neve to Monterey, and Captain Rivera was transferred to Loreto, the former capital of the coastal provinces. In his new position, Rivera’s authority was restricted, and one of de Neve’s first orders to him was to result in the death of that unfortunate officer and furnish a tragic episode in mission history.

Fernando Rivera was settled at his post in Loreto when de Neve’s fateful orders arrived. The Captain was instructed to take a company of soldiers to the northwest provinces of Mexico and bring back as many families of new settlers as possible. Although Rivera found many people who were living in privation, he could induce only a few to make the trip to California despite the promise of fertile lands and new belongings.

Yuma Indians attack at the Colorado River

When Rivera arrived at the Colorado River, he sent the emigrants onto the coast with part of his company as escort. With the remainder of his military complement, he planned to set out again in search of additional colonists. However, a few days after the emigrant party had departed, the Yuma Indians killed him and all of his soldiers in a surprise uprising. Captain Fernando Rivera died on July 18, 1781, at Mission San Pedro y San Pablo de Bicuñer, Arizona.

De Anza’s overland route to Mexico is closed

Two mission establishments were also attacked and destroyed. These were not part of the California chain, but Father Carces, whose travels and writings are so vitally linked to the history of El Camino Real, was killed in the attack. The authorities in Mexico were quick to blame Juan Bautista de Anza for giving a false description of the docility of the Yuma Indians, and the uprising resulted in the closing of the overland route to Mexico. From this time onward, the Spanish colonies of California were forced to depend upon the sea lanes. The abandonment of the Colorado crossing by Mexico left the way open to the east and the trail was re-opened by the Americans in 1849.

Mission Santa Clara de Asís today

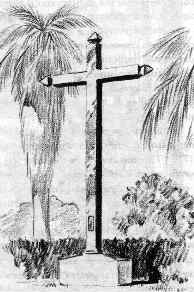

All that remains in the history of Mission Santa Clara de Asís, which dates back to 1777, is written today in the cloister garden wall and the piece of cross that was part of the first dedication ceremony. This fragment, encased within a large concrete cross, stands in front of the beautiful new church that was erected after the fire of 1926 in a faithful reproduction of the original design.