Thirteen days after he dedicated Mission San José, Father Lasuén was at San Juan Bautista, where he performed a like ceremony. Mission San Juan Bautista joined the growing chain of Franciscan establishments on June 24, 1797. Within six months, Mission San Juan Bautista held an adobe church, a monastery, a granary, barracks, a guardhouse, and adobe houses for the Native converts.

Growth of Mission San Juan Bautista

By 1800, over 500 Indians were living at Mission San Juan Bautista. An earthquake caused substantial damage in October of that year. The Mission Padres exploited such a nefast event to enlarge the Mission Church and add new facilities while making the necessary repairs. The Indian population continued to increase, and in 1803, the Franciscans made extensive plans to build another Church. An elaborate ceremony preceded the construction work, and people from all over the province attended it. During the dedication, the Padres sealed a story of the event in a bottle and placed it within the cornerstone.

A Large Church of Three Naves

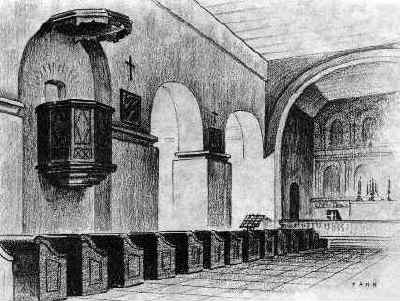

In 1808, a new Padre named Father Arroyo de la Cuesta arrived, bringing tremendous energy, learning, and imagination. Instead of the usual long and narrow nave, Father de la Cuesta convinced the builders that a large church of three naves would be an unusual asset to San Juan. When the Mission inhabitants completed the Church in 1812, this was the largest in the province and the only such structure ever built by the Franciscans in California.

While the work progressed on the church building, the neophyte congregation for whom it had planned began a fast decline. In 1805, the Indian population had stood at 1,100. By 1812, when the new Mission Church was completed, death and desertions had reduced the number of Indian converts by more than half. The new layout dwarfed the attending congregations, and Padre de la Cuesta walled in the two rows of arches separating the three naves of the Church. Except for the area near the altar, with such modification, the interior resembled other mission churches, with the two outside naves forming large separate rooms.

Thomas Doak, the First American of California

However, the energetic Padre did not deny decorating and furnishing the San Juan Bautista Mission Church. He continually sought needed religious articles with an appreciative eye for the finest available artisanship. In 1820, he hired Thomas Doak, an American carpenter gifted with a decorative talent, and embellished the church interior walls. Incidentally, Thomas Doak was the man who deserted his ship and came ashore at Monterey in 1816 to become the first American citizen to settle in California. He took Spanish citizenship, found a permanent home at Mission San Juan Bautista, and married one daughter of Californio politician José Castro.

Spanish military use San Juan as a supply base

In 1790, the Spaniards began showing considerable interest in the lands east of El Camino Real. San José, San Juan Bautista, and Soledad reflected this interest. Spaniards no longer avoided the unfriendly Indian tribes, and in the ranks of the military, such names as Vallejo, Amador, Moraga, and Peralta became prominently connected with Indian fighting. Under the leadership of one or more of these men, groups of soldiers constantly visited San José and San Juan Bautista and used them as supply bases.

Mission del Rio de los Santos Reyes

Fighting was not the only method of approaching the Native pagans, for the Franciscans never discarded the idea of establishing other Missions to the east. One of the most curious consequences of this missionary zeal was the Mission del Rio de los Santos Reyes, which, in fact, never existed.

The Boston stonemason Caleb Merrill

In 1831, a Boston stonemason, Caleb Merrill, arrived at Mission San Diego. The Franciscans appreciated his services at once, and it was not long before he was working at Mission San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo. A short time later, a missionary expedition arrived at San Juan Bautista, leaving behind a pile of adobe masonry still evident in the 1860s.

Father Estévan Tápis

In 1812, Father Estévan Tápis, who had been acting as Father President of California Missions since the death of Father Fermín de Lasuén in 1803, retired from the office and joined Father de la Cuesta at San Juan Bautista Mission. Like Father Narciso Durán, he had a musical talent, and it was he who did so much to develop choral singing among the Indian neophytes.

While staying at Mission San Juan Bautista, Father Estévan Tápis seemingly introduced the use of colored notes to identify the various vocal parts on the music sheet. In the favorable surroundings of San Juan Bautista, the elderly Franciscan consumed the last of his 71 years. Mission dwellers and other Franciscans mourned him widely when he died in 1825.

Father Arroyo de la Cuesta

Father de la Cuesta continued to relegate the affairs of Mission San Juan Bautista until its administration passed into the hands of the Zacatecan Franciscans. He was a forceful and imaginative man with a background and education richer than most of his fellow friars. One of his pleasures was endowing his newborn charges with names borrowed from the past. In this connection, Alfred Robinson, the American hide dealer who visited San Juan, related that the place abounded in “infant Platos, Ciceros, and Alexanders”.

Father de la Cuesta knew more than a dozen Indian languages and could deliver his sermons in seven tongues. During his stay at San Juan Bautista, he wrote two important works: one was a compendium of Indian phrases, and the other was an exhaustive study of the Mutsumi language that received scientific recognition in 1860. The Mission acquired an English barrel organ in 1826, and this crank-operated music maker produced wonder and enjoyment for the Indian converts. Several legends grew around this marvelous instrument, one of which gave it unusual powers and linked it with the founding of Mission San Juan Bautista.

Zacatecas take control of the Mission

After Father de la Cuesta turned the direction of the Mission over to the Zacatecas upon their arrival in 1833, he joined his own Franciscans at San Miguel, where he remained until he died in 1840. The Zacatecan period was over in a brief two years. In 1835, with the Secularization Act, San Juan Bautista was reduced to a curacy of the second class, controlled by a Civil Administrator who soon liquidated its assets. In place of the Indian village, a little settlement of whites materialized near Mission San Juan. The settlement counted some 50 inhabitants by the end of 1839.

The Pueblo of San Juan Bautista

The new Pueblo became the town of San Juan Bautista, whose history is one of romance, stirring pioneer days, and much bloodshed. Through all these turbulent times, kindly Padres lived at the Mission of San Juan Bautista, as they do today, administering to the community’s religious needs. From the day of its founding, the Mission never lacked a spiritual guide or a pastor and, on November 19, 1859, President James Buchanan returned San Juan Bautista to the Catholic Church.

The 1860 Bell Tower or Campanario

The wooden tower, built around 1860 and later duplicated in concrete, has been a part of the Mission for so long that when its removal was announced earlier in 1950, the old residents of the area were genuinely fearful that the structure was being desecrated. The tower, which was not in harmony with the rest of the old Mission Church, was added by a secular priest to make his tasks a little easier. It permitted the ringing of the church bells no matter how the weather was, and, since he could not afford to pay the wages of an attendant, his action reveals a practical rather than an artistic nature.

The Earthquake of 1906

After the secular priest departed, the earthquake of 1906 did extensive damage to the Church. Fortunately, the Monastery was not affected, and the new Padre did his best to restore the Church, although both outside naves were damaged and had to be abandoned.

Mission San Juan Bautista Today

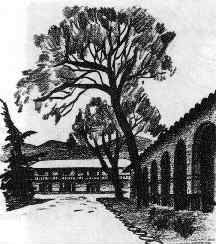

Today Mission San Juan Bautista faces a most remarkable plaza. On it, there is a hotel, a stable, and two adobe mansions, all identical to the appearance of 100 years ago. In 1933, the United States Government acquired the Plaza Hotel, with its wonderful barroom, the old Castro House, the wagons of the livery stable, and the clumsy and elaborate beds in the Zanetta house. Today, these old structures combine to give a vivid picture of how California was just before the Gold Rush Days. There are no false fronts or artful imitations. These are the actual buildings of the community which stood near the beautiful old Mission.

During 1976-77, the earthquake damage to the mission church of San Juan Bautista was at last repaired. Both side naves are now open, and the campanario, or bell wall, was rebuilt.