In the Valley of the Bears, so named by Don Gaspar de Portolá and his men on their first expedition from San Diego north in search of Monterey Bay in 1769, Father Junípero Serra founded Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa, fifth in his chain of Franciscan stations, on September 1, 1772.

Portolá discovers the Valley of the Bears

Progressing slowly on their march northward, Portolá and his soldiers encountered many ferocious bears between the mouth of the Santa Maria River and the present site of San Luis Obispo and killed some of them for food. In their vivid diaries of the journey, Fathers Juan Crespí and Francisco Gomez expressed astonishment at the large number of bears. When starvation threatened the early settlements, they wrote, a hunting party sent out by Portolá returned with more than 9,000 pounds of bear meat. A few months later, the Franciscans established Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa at the scene of this hunt.

In August of 1772, Father Serra received word at his mission in Monterey that the San Carlos and the San Antonio had arrived in San Diego with supplies. The two ship Captains shared a dark view of their previous journeys to the north and had mutually decided that San Diego would be as far north as they would venture. They forwarded this opinion to Father Serra, suggesting to carry the supplies overland from the southern port. Father Serra immediately set off for San Diego, determined to persuade at least one Captain to sail to Monterey.

Founding of Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa

To capitalize on his journey, he took another Franciscan and gave him the responsibility of establishing the Mission of San Luis Obispo de Tolosa. He was reluctant to leave only one Franciscan Father at the mission. He feared that the military might seek to make a rule out of this exception to reduce the stature of the missions. As an impulsive man as he was, in the end, the decision Father Junípero took turned out very well. Mission San Luis Obispo grew. Months before, after killing several bears, the Spaniards had shared the meat with local hungry Natives. This generosity reaped a harvest of goodwill towards the Spanish once they made early contact with nearby Indians.

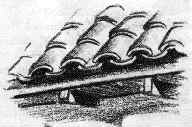

San Luis Obispo is set afire three times

Nonetheless, hostile Indians attacked Mission San Luis Obispo on three separate occasions before 1774, and the thatched roofs of the mission buildings were set afire by blazing arrows. Up to this time, most of the missions used thatched roofs above their adobe walls. As a result of many fires, the Padres developed a roof tile to protect the structures. Soon, all missions benefited from this step, and tile replaced thatched roofs throughout the mission chain.

An interesting sidelight is that Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa, though one of the smallest, contributed its share of an assessment levied against the California Franciscans in 1782 by the King of Spain to help him carry on his war on England. On the occurrence, San Luis Obispo de Tolosa sent $107 to Spain.

The Golden Age of Mission San Luis Obispo

From 1794 to 1809, building operations at San Luis Obispo were quite extensive. In 1804, the number of neophytes peaked at 832, and by the end of that year, the records show 2,074 baptisms and 2,091 deaths. In May 1807, the mission was designated as one of six in which the California Padres could make their annual retreats for spiritual exercises. Beginning in 1811 and continuing through 1820, the Missionary Fathers erected numerous dwellings for their converted Indians and made many improvements and additions to the mission. In 1819, the construction of the quadrangle was completed. Furthermore, the arrival of two mission bells from Lima, Peru, a year later, was a particularly glorious occasion.

Father Luis Martinez of San Luis Obispo

Following the Mexico Revolt against Spain in 1810, all California missions were obliged to contribute food and clothing to the army, which the Government had ceased to support. At San Luis Obispo, Father Luis Martinez often found himself and his Indian wards suffering great privations because of the constant requests from the military.

Father Martinez was a jovial soul. His wit and good humor won him widespread fame in those early days. His sarcastic comments on the idleness of the soldiers stirred up trouble in 1816, but, two years later, he was restored to the good graces of the army when he valiantly led a company of his Indians to Santa Barbara and San Juan Capistrano many leagues distant to help defend the missions against two shiploads of South American privateers.

Legend has it that Father Martinez, on the occasion of a visit from a distinguished General and his bride, arranged to have the entire barnyard population march in a solemn review before his celebrated visitor. Unfortunately, the doughty Padre’s quick temper and outspoken criticism led to difficulty with the Governor. Eventually, his enemies grew strong enough to drive him out of the country. In 1830, after 34 years of service, he was forced to leave his beloved Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa. The account tells of his sorrow at the parting. But as the mission fell victim to land reformers only five years later, it was perhaps a happier end than the later days would have brought him.

San Luis Obispo and Mexican Governors

The history of the ruin of San Luis Obispo de Tolosa under successive Mexican Governors is similar to that of the other missions of California, all of which have been fully recorded. It is interesting here to note that the Spanish occupation of Alta California was one of the best-documented colonizing efforts ever made by a civilized nation. Considering the primitive nature of their environment, the number of records, accounts, census figures, and personal diaries produced by the early Californians is truly amazing. From the very first years, a constant stream of exports flowed back to Mexico City, the Viceroy, the Franciscan College of San Fernando, friends, and former companions.

The question of postage payment

The magnitude of the scripts was so great that one of the chief points of conflict between Civil and Religious Leaders was the question of postage payment. Some of this undoubtedly resulted from the eagerness of the Governors and the Mission Leaders to acquaint their Superiors with their interpretations of the issues in dispute. In any event, not even the slightest incident seems to have escaped the record books.

Mission San Luis Obispo today

Today, the San Luis Obispo de Tolosa Mission is an important element in the life of the city of San Luis Obispo, which proudly calls itself “The City with a Mission”. The mission now serves as a modern parish church for the many Catholics in the area. The original Padres residence has been turned into an extraordinary mission museum and hosts an extensive collection of early photographs. Other items present a vivid picture of the way of life in California before the turn of the century.